Health Promotion Perspectives. 13(1):21-35.

doi: 10.34172/hpp.2023.03

Systematic Review

COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy: A Systematic review of cognitive determinants

Sara Pourrazavi Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Validation, Writing – original draft, 1, 2

Zahra Fathifar Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, 3

Manoj Sharma Writing – review & editing, 4, 5

Hamid Allahverdipour Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, 1, 2, *

Author information:

1Research Center of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran

2Health Education & Promotion Department, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran

3Department of Library, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran

4Department of Social and Behavioral Health, University of Nevada, Las Vegas (UNLV), Las Vegas, NV 89119, USA

5Department of Internal Medicine, Kirk Kerkorian School of Medicine at UNLV, Las Vegas, NV 89154, USA

Abstract

Background: Although mass vaccination is considered one of the most effective public health strategies during the pandemic, in the COVID-19 era, many people considered vaccines unnecessary and, or doubted the effectiveness of the COVID-19 vaccine. This review aimed to tabulate cognitive causes of COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy, which may help public health policymakers overcome the barriers to mass vaccinations in future pandemics.

Methods: For this systematic review, studies pertaining to COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy published up to June 2022 were retrieved from six online databases (Cochrane Library, Google Scholar Medline through PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science). Inclusion criteria were the studies conducted on people who had a delay in accepting or refusing COVID-19 vaccines, reported the impact of cognitive determinants on vaccine hesitancy, and were written in English in the timeframe of 2020–2022.

Results: This systematic review initially reviewed 1171 records. From these 91 articles met the inclusion criteria. The vaccination hesitation rate was 29.72% on average. This systematic review identified several cognitive determinants influencing vaccination hesitancy. Lack of confidence and complacency were the most frequent factors that predicted vaccine hesitancy.

Conclusion: The identified prevailing cognitive determinants for COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy indicated that using initiative and effective communication strategies would be a determinant factor in building people’s trust in vaccines during the pandemic and mass vaccinations.

Keywords: COVID-19 vaccines, Vaccination hesitancy, Cognitive psychology, Systematic review

Copyright and License Information

© 2023 The Author(s).

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Introduction

The outbreak of the COVID-19 disease caused an emergency situation worldwide by affecting various aspects of human life. Although preventive measures, such as social distancing, wearing face masks in public, being under lockdowns, and quarantines helped to control COVID-19 virus transmission, returning to normal life urgently needed long-term solutions such as universal vaccination.1 COVID-19 vaccine reduced the mortality rate of disease and consequently had many benefits on the health and socio-economic aspects of life in the COVID-19 era.2 Additionally, the vaccines against the coronavirus changed the course of the pandemic to a better status by reducing the severity of COVID-19 disease and the incidence of new cases, even among unvaccinated people, through herd immunity.2 However, the COVID-19 vaccine, like all other new vaccines, faces the age-old public acceptance problem.3 Therefore, not only discovering and making available the COVID-19 vaccine is one of the critical challenges for the policymakers, but it will also be essential to encourage people to get it.4

Even though the effectiveness and safety of many vaccines, such as COVID-19, have been well established, many people consider vaccines unnecessary and doubt their effectiveness and safety.2 Vaccine hesitancy is defined as a postponement in acceptance or denial despite the availability of a vaccine.5 It has been declared one of the top 10 warnings to attaining health for all by the World Health Organization (WHO).2

Vaccine hesitancy has existed since the advent of the vaccines for influenza, human papillomavirus, polio, measles, etc.3 Recently, the world has witnessed people’s hesitation to receive the COVID-19 vaccine.6 COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy threatened doubtful people and the entire society by delaying the threshold of vaccine uptake necessary to achieve herd immunity.2 The acceptance rate of the COVID-19 vaccine in different countries varied from the lowest of 23.6% in Kuwait to 97% in Ecuador.6 In contrast, for successful control of COVID-19, the vaccine hesitancy should not be more than 25%-30%.7

Many reasons can cause doubts about the COVID-19 vaccination, including fear of probable side effects, concern about the rapid vaccine production process, fear of inefficiency, unpleasant effect on some specific diseases,5 lack of trust in clinical trials, the sufficiency of the immune system to fight against COVID-19,2 the spread of fake information and news,7 religious beliefs,8 and political ideology.9 Therefore, the hesitancy of COVID-19 vaccination is not an individual problem; rather, it is a complex, multifaceted behavior that can have different cognitive, behavioral, social, and even political reasons in different societies and times. Although recent literature has investigated its reasons from different perspectives, little cumulative evidence has attempted to summarize in-depth and systematically the cognitive causes of COVID-19 Vaccine hesitancy. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to review the cognitive determinants of hesitancy toward COVID-19 vaccine.

Materials and Methods

Study design and search strategy

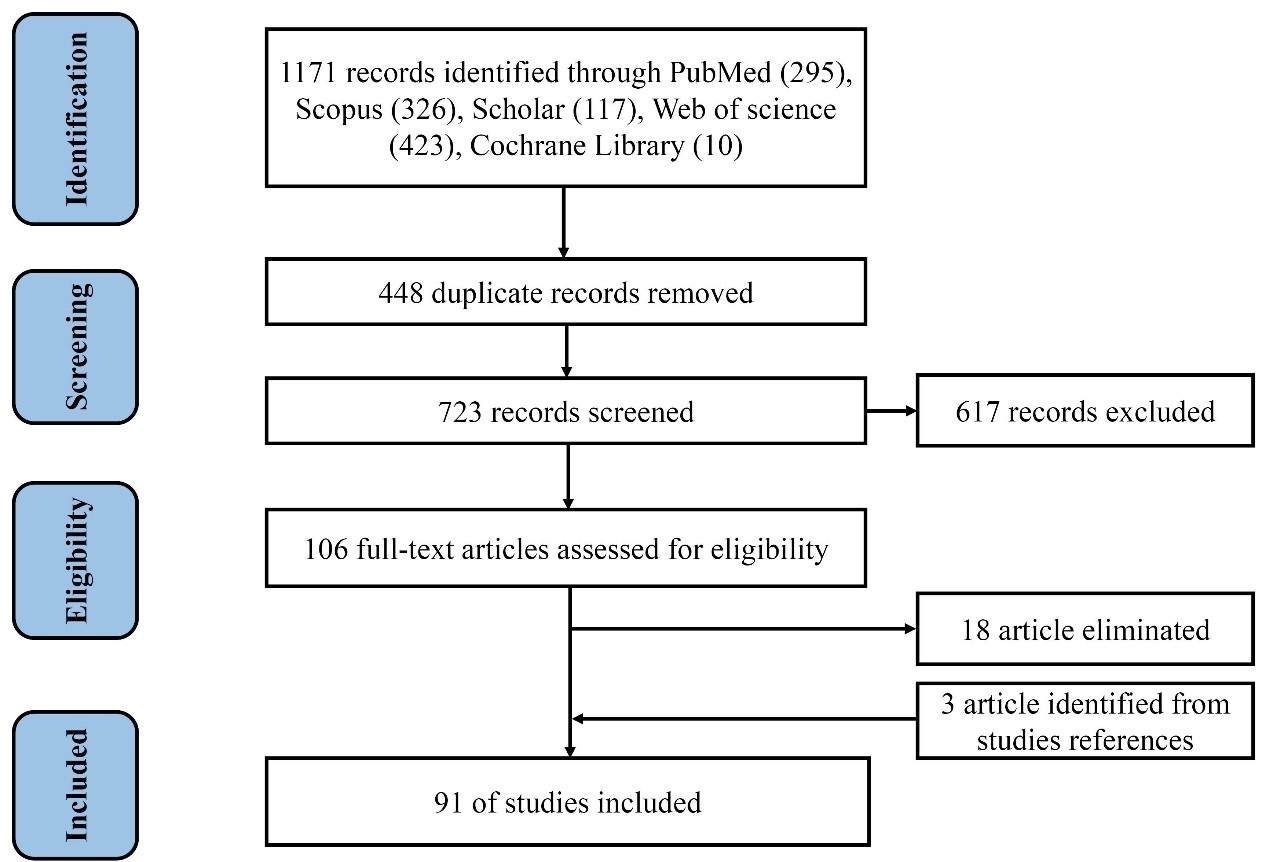

Six online databases (viz., Cochrane Library, Google Scholar Medline through PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science) were searched thoroughly using a methodical approach in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines to identify relevant studies.10 We utilized the study’s research question to drive the search terms, namely, “what cognitive determinants influence COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy?” Therefore, the selected keywords were structured with Boolean operators. An example of this search strategy applied to the PubMed database is available in Supplementary file 1. After removing duplicates, the screening phase generated 723 articles. Moreover, we examined the references of identified publications for relevant studies.

Study selection

Eligibility criteria were established beforehand using the PICO (population, intervention, comparison, and outcomes) design, and the research team (SP, ZF, HA) examined and approved the content validity:

Populations. Articles that included people who had delayed acceptance or refusal of COVID-19 vaccines despite its availability. No additional restrictions on population are considered.

Comparison. No criteria for comparison were applicable.

Outcomes. Any reported impact of cognitive determinants on vaccine hesitancy.

Time. All peer-reviewed journal articles published between January 2020 and June 2022 were included.

Setting. No limitations on the type of settings were imposed.

English language quantitative (cross-sectional studies, randomized controlled trials, non-randomized studies, pre-post studies, and time series) or mixed methods (focused on the quantitative strand) research were eligible study designs. Systematic reviews were excluded but were employed to identify additional eligible studies.

The search strategy was conducted in accordance with the Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies statement.11 To ensure whether studies met the inclusion criteria, two authors conducted separate searches, screen the titles and abstracts, and then assessing the remaining 106 publications’ full texts.

Screening the full-text and synthesis

For evaluation studies, information extracted included details about study characteristics, participants, setting, the prevalence of hesitation, and the findings related to the outcomes of interest.

Two research team members, SP and ZF, independently pilot-tested the data extraction form utilizing two of the 106 articles and compared and discussed the findings. The feedback was used to refine the form. The final draft of the form was used by SP to extract data from the remaining 104 articles, which were independently checked by ZF. Title and abstract screening, along with full-text screening and cross-validation, were conducted by two review authors (SP and ZF) independently based on the abovementioned inclusion criteria. Any disagreements over a particular study were resolved through mutual discussion with a third reviewer (HA). Subsequently, 18 of the 106 articles were removed, resulting in a final included sample of 88 studies. Studies were excluded if they did not evaluate hesitancy toward COVID-19 vaccine and just measured vaccine acceptance. In addition, those studies which have not pointed out the role of cognitive determinants in hesitancy to the COVID-19 vaccine were eliminated.

We added three additional articles to our enumeration by reviewing the references from the articles. Figure 1 depicts the selection process over four-rounds. Using the PRISMA flow diagram, the documentation and summarization of the identification, screening, eligibility, and selection processes was done. Finally, at total of 91 articles were independently reviewed by SP and ZF. After that relevant data were extracted, and if there were any discrepancies, they were resolved for 100% agreement.

Figure 1.

The diagram of the study based on PRISMA checklist

.

The diagram of the study based on PRISMA checklist

Quality assessment

Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement was used to conduct qualitative assessment independently with the help of two reviewers (SP and ZF).12 This checklist incorporates 22 criteria. If a study meets a condition, it receives one point, or zero if it is not or only partially disclosed. In this rating a higher overall score means that there is less of methodological bias. We divided each study’s risk of bias score by 22 (the highest possible score) and then multiplied it by 100 to assess the proportional percentage of fulfilled criteria. Any dissenting issues between the reviewers were resolved through discussion and consensus with the help of a third reviewer (HA). Studies’ quality were then sorted into excellent (matching ≥ 85% criteria), good (matching 70 to < 85% criteria), fair (matching 50 to < 70% criteria), and poor (matching < 50% criteria).13

Results

Descriptive findings

This review considered 91 peer-reviewed publications. The investigation comprised COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy studies from 36 different countries. Most surveys were conducted in the United States (n = 15), followed by China and Italy (n = 8 for each country), and Bangladesh (n = 7). Numerous studies were carried out in more than one country.14-18 The study carried out among US households3 had the largest sample size (n = 459 235), while one study carried out among homeless people in the US had the smallest sample size (n = 90).19 Out of these 91 studies, 27 were conducted with the general population, 27 with adults, 11 with health care workers, 10 with students, 7 with patients, 3 with parents/guardians, and 9 with other people such as pregnant women, homeless people, and refugees (Table 1).3,5,6,8,9,14-99

Table 1.

Cognitive determinants of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy

|

Author(s)

|

Population & country

|

Hesitancy rate

|

Results

|

Author(s)

|

Population & country

|

Hesitancy rate

|

Results

|

| Abedin, 202121 |

3646 adults from

Bangladesh |

8.5 % reluctant |

Confidence in the country’s healthcare system |

Al-Sanafi & Sallam

202122 |

1019 HCWs from Kuwait |

9.0% |

The belief that the virus had a human-made origin |

| Adane et al, 202223 |

404 HCWs from Ethiopia |

36.0% refused |

Anti-vaccine attitudes

Poor knowledge and perception |

Al-Mistarehi et al, 2021

24 |

2208 individuals from Jordan |

- |

Lack of trust in the vaccine and their companies

Lack of enough information

Fear of side effects

Concerns about safety and effectiveness

Anti-vaccine attitudes |

| Adigwe, 202125 |

1767 individuals from Nigeria |

- |

Concerns about side effects |

Alrajeh, et al, 202126 |

401 adults from KSA |

- |

Perceived susceptibility

Perceived benefits

Perceived barriers

Concerns about effectiveness, safety, false vaccination, and side effects |

| Aemro et al, 202127 |

440 HCWs from Ethiopia |

45.9% hesitate |

Unclear information provided by public health authorities

Low perceived threat

Concerns about side effects |

Alzubaidi, 202128 |

669 students from UAE |

31.8%

hesitant |

Risks perception versus vaccine benefits

Concerns about safety and effectiveness

Attitudes about the disease and its consequences

Knowledge and awareness about the vaccine

Personal, family, and community experience with vaccination and feelings of solidarity

Perception of the pharmaceutical industry

Lack of confidence in government policies |

| Afzal et al, 202229 |

3759 HCWs from the US |

- |

Concerns about rushed vaccine development

Fear of side effects

Lack of trust in the people advocating for the vaccines

Anti-vaccine attitudes |

An et al, 202130 |

854 students from Vietnam |

- |

Concerns about side effects, safety, effectiveness, and rushed vaccine development

Fear of needles

Low perceived susceptibility

Lack of confidence in government |

| Aguilar Ticona et al, 202131 |

985 non-pregnant participants from Brazil |

26.1% were hesitant and

7.9% unsure |

Concerns about effectiveness and side effects |

Ashok et al, 202132 |

264 HCW from India |

- |

Concerns about rushed vaccine development

Lack of enough information |

| Al-Ayyadhi et al, 202120 |

6943 adults from Kuwait |

74.3% hesitant |

Concerns about safety and side effects

Believing conspiracy theories |

Badr et al, 202133 |

1208 adults from the US |

526 people were hesitant |

Low perceived susceptibility

Perceived the vaccination process as being more convenient |

| Baccolini et al, 202134 |

5369 students from Italy |

22% to 29% hesitancy ranged |

Low perceived susceptibility and severity

Concerns about safety and effectiveness

Concern for the emergency |

Chaudhary et al, 202135 |

410 patients and their attendants from Pakistan |

47.3% were hesitant |

Lack of knowledge Understanding the way vaccines work

Concerns about vaccine efficacy, safety, and comfort in the vaccine administration |

| Balan et al, 202136 |

1581 students from Italy |

8% undecided group |

Rushed vaccine development

Vaccine barriers outweigh benefits

Belief in natural immunity

Lack of trust in the vaccine

Lack of trust in the local and medical authorities |

Costantino et al, 20215 |

346 patients from Italy |

25.2% were hesitant |

Fear of adverse events

Concerns about rushed vaccine development

Not afraid of COVID-19

Uncertain of vaccine efficacy |

| Blanchi et al, 202114 |

417 patients from Europe, France, and Italy |

18.9% were hesitant |

Confidence in getting the vaccine easily

Concerns about side effects and efficacy

Lack of trust in scientists and the healthcare system |

de Sousa Á et al, 202137 |

6843 individuals from Portugal |

21.1% were hesitant |

Perceived high stress

Afraid of future repercussions of the disease

Vaccine Conspiracy Beliefs and misinformation |

| Bolatov et al, 202138 |

888 students from Kazakhstan |

70.7%-75.5% |

Trust in the opinions of close relatives

Concerns about side effects, safety, effectiveness, and quality

Belief in natural immunity |

Du et al, 202139 |

3011 reproductive women from China |

8.44% children and 3,011 reproductive women were hesitant |

Low perceived susceptibility

Lower perceived benefit

High perceived barriers |

| Bou Hamdan et al, 202140 |

800 students from Lebanon |

10% were hesitant |

Concerns about vaccine safety

The vaccine in agreement with their personal views

Agreement with conspiracies

Level of knowledge about COVID-19 disease and vaccine

Disagreement with that symptomatic cases are the only carriers of SARS-CoV-2 |

Ebrahimi et al, 202141 |

4571 adults from

Norwegian |

10.46% were hesitant |

Perceived risk of vaccination

Belief in the superiority of natural immunity

Lack of confidence in government

Fear of infecting significant others |

| Butter et al, 202242 |

1599 adults from the UK |

17.7% uncertain, 8.1% refuse |

Low perceived susceptibility |

Ehde et al, 202143 |

359 Adults from the US |

20.3% were hesitant |

Low perceived susceptibility

Low trust in the Centers for Disease Control and

Concerns about side effects, vaccine approval process, and potential impact of the vaccine given their health conditions |

| El-Sokkary et al, 202144 |

308 HCWs from Egypt |

41.9% were hesitant |

Perception for the severity of COVID-19

COVID-19 vaccine safety

Anti-vaccine attitudes |

Ghaffari-Rafi et al, 202145 |

359 adult patients from US |

- |

Concerns about vaccine safety

Self-perception of a preexisting medical condition contraindicated with vaccination |

| Fares et al, 202146 |

385 HCWs

from Egypt |

51% undecided

28% refused |

Lake of enough clinical trials

Fear of side effects of the vaccine |

Gomes et al, 202247 |

3232 individuals from Portugal |

11% were hesitant |

Feeling agitated, sad, or anxious

Low or no confidence in the health services’ response

Perceived measures implemented by the government as inadequate

Low perceived susceptibility

Concerns about safety and effectiveness |

| Fedele et al, 202148 |

640 individuals from Italy |

50%

not sure |

Concerns about side effects, safety, and effectiveness

Opposition to vaccines

Other non-specific reasons |

Griva et al, 202149 |

1623 adults from Singapore |

9.9% were hesitant |

Concerns about side effects, safety, and rushed vaccine development.

Low perceived threat

Lack of trust in the vaccine

Low perceived benefits

Lower moral and subjective norms |

| Freeman et al, 202150 |

5114 adults from UK |

16.6% unsure

11.7% hesitant |

Beliefs about a COVID-19 vaccine

Mistrust |

Hwang et al, 202151 |

13021 individuals from Korea |

39.8% were reluctant or refused |

Concerns about safety and side effects

Complacency toward COVID-19

Awareness of the preventive guidelines

Lack of confidence in government

No fear of COVID-19 |

| Genovese et al, 202252 |

4116 individuals

from Italy |

17.5% were doubtful. |

Lack of trust in the vaccine

Low perceived susceptibility

Fear of side effects |

Hossain, et al, 202153 |

1377 individuals from Bangladesh |

35.25% unsure

18.99% denied |

Concerns about side effects, safety, and efficacy

Against the vaccination program

Afraid of taking injections

Belief in natural remedies |

| Gerretsen et al, 202115 |

7678 adults from US and Canada |

The mean (SD) hesitancy 2.3/6.0 (1.6) |

Low perceived seriousness

Low perceived threat

Low perceived susceptibility

Mistrust in vaccine benefit

Preference for natural immunity

Lack of confidence in government

Risk propensity

Mistrust in others

The negative impact of COVID-19 on mental health |

Hossain et al, 20216 |

1497 adults from Bangladesh |

41.1% were hesitant |

Perceived susceptibility and severity

Perceived benefits and barriers

Anti-vaccine attitudes

Subjective norm

Perceived behavioral control

Anticipated regret

Lack of trust in the vaccine

Complacent

Calculative

Collective responsibility |

Jain et al,

202154 |

1068

students from India |

10.6% were hesitant |

Concern about safety and efficacy

Lack of awareness regarding their eligibility for vaccination

Lack of trust in the government |

Li et al, 202155 |

2196 students from China |

41.2% were hesitant |

Perceived severity

Concerns about side effects and effectiveness |

| Kanyike et al, 202156 |

600 students from Uganda |

30.7% were hesitant |

Concerns about side effects

Low perceived threat

Belief in acquiring immunity against COVID-19 |

Liddell et al, 202157 |

516

refugees living from Australia |

28.1% were hesitant |

Trust barriers

Lower logistical barriers

Attitudes relating to low control

The Risk posed by COVID-19 |

| Khairat et al, 202258 |

3142 adults from the US |

Mean (SD) 8 (2.83) hesitant |

Lack of trust in the vaccine

Concerns about side effects

Lack of confidence in government |

López-Cepero et al, 20218 |

1911 adults from the US |

More than 6.5% no intent

11% unsure |

Lack of trust in the vaccine

Unafraid of getting COVID-19

Not worried about getting COVID-19

Barriers to getting the vaccine

Concerns about efficacy, safety, and novelty

The rigor of vaccine testing

Lack of confidence in government |

| Knight et al, 202159 |

762 individuals from UK |

22% were hesitant |

Confidence

Complacency

Convenience |

Luk et al, 202160 |

1035 individual from

China |

29.2% undecided

25.5% no intention |

Concerns about safety, side effects, and effectiveness

Knowledge of SARS-CoV-2 transmission

Perceived danger of COVID-19 |

| Kucukkarapinar et al, 202161 |

3888 adults from Turkey |

43.9%-58.9%

Increased rate of vaccine hesitancy/refusal |

Conspiracy thinking

Less knowledge of prevention

Reduced risk perception

Higher perception of media hype

Trust in the Ministry of Health and medical professional organizations |

Marijanovic et al, 202162 |

364 patients from Bosnia and Herzegovina |

37.6% Not sure |

Doubt about the results of clinical trials of COVID-19 vaccines |

| Kuhn et al, 202119 |

90 homelessness from the US |

48% were hesitant |

Fear of side effects

Rejection of all vaccines

Less trust in COVID-19 information from official sources, media, and friends

Perceived threat |

McCarthy et al, 20219 |

779 patients from Australia |

30.6% were hesitant |

Vaccine conspiracy theory

Having higher perceptions of anomie

Lack of confidence in government

Low perceived health threats |

| Lee & You 202263 |

1016 individual from

South Korea |

53.3% were hesitant |

Perceived susceptibility

perceived benefits

Perceived barriers

Lack of confidence in government |

Moujaess et al, 202164 |

111 Patients from Lebanon |

30.6% were hesitant |

Desire to know more about the consequences of the vaccine in other patients with cancer |

| Muhajarine et al, 202165 |

9252 adults from Canada |

13 % were unsure, and 11% refused |

Low perceived threat

Low perceived severity

Not concerned about spreading the virus |

Orangi et al, 202166 |

4136 individuals from Kenya |

36.5% were hesitant |

Low perceived threat

Concerns about side effects and effectiveness |

| Murphy et al, 202118 |

Ireland = 1041 and UK = 2025 individual |

35% hesitancy for Ireland

31% hesitancy for England |

Low trust in scientists, healthcare professionals, and the state

Negative attitudes toward migrants

Lower levels of altruism

Higher levels of conspiratorial

Lower levels of agreeableness

Higher levels of internal locus of control

Lower levels of the conscientiousness

Higher levels of neuroticism

Belief in chance

Beliefs about the role of powerful others |

Patwary et al, 202167 |

543 adults from Bangladesh |

15% were hesitant |

Perceived barriers

Subjective norms

Low perceived threat

Anti-vaccine attitudes

Less self-efficacy

Concerns about side effects and effectiveness

Lack of enough information

Belief in natural immunity |

| Navarre et al, 202168 |

1964 HCWs

from French |

46.6% opposition to vaccination |

Lack of trust in health authorities |

Park et al, 202169 |

902 individuals from South Korea |

20.8 % were hesitant |

Low perceived threat

Concerns about safety

Affective and Cognitive risk perception of COVID-19

Perceived the government’s performance as ineffective |

| Nazlı et al, 202170 |

467 18-65 years old from Turkey |

13.2% were hesitant |

Belief in conspiracy theories low fear of COVID-19 |

Paschoalotto et al, 202171 |

1623 individuals from Brazil |

30% were hesitant |

Concerns about side effects |

| Nery et al, 202272 |

2521 individuals from Brazil |

18.6% were hesitant |

Low perceived threat |

Pedersen et al, 202116 |

423 individuals from 31 countries |

4% were hesitant |

Concerns about side effects, rushed vaccine development, and effectiveness

Lack of enough information |

| Nguyen et al, 202173 |

651 pregnant women from Vietnam |

- |

Concerns about safety and effectiveness |

Peirolo et al, 202174 |

776 HCWs from Switzerland |

- |

Low perceived threat

Concerns about side effects |

| Okubo et al, 202175 |

23142 individuals from Japan |

11.3% were hesitant |

Concerns about adverse reactions

Doubts about the vaccine efficacy

Low perceived susceptibility |

Prickett et al, 202176 |

1284 individuals

from New Zealand |

14.2% were unlikely and 15.1% unsure |

Concerns about the side and future effects

Thought their chances of becoming seriously ill if they caught COVID-19 were low

Being protected by herd immunity |

| Rahman et al, 202177 |

850 adults from Bangladesh |

30.23% were hesitant |

Afraid of side effects

lack of enough information

Lack of trust in the vaccine |

Schernhammer et al, 202278 |

1007 adults from Australia |

41.1% were hesitant |

Optimism |

| Reno et al, 202179 |

1011 individuals from Italy |

31.1% were hesitant |

Perceived threat |

Shekhar et al, 202180 |

3479

HCWs from the US |

56% were hesitant |

Concerns about Safety, efficacy, and rushed vaccine development |

| Roberts et al, 202281 |

1004 adults from the US |

- |

Anti-vax beliefs |

Shen et al, 202182 |

2361 individuals from China |

- |

Lack of trust in the vaccine

Risks perception |

| Ruggiero et al, 202183 |

427 parents from the US |

21.93% were hesitant |

Concerns about side effects and safety |

Soares et al, 202184 |

1943 individuals from Portugal |

56% wait and 9% refuse. |

Lack of trust in the vaccine and the health service response

Worse perception of government measures

Perception of the information provided as inconsistent and contradictory |

| Schaal et al, 202185 |

2339 pregnant & breastfeeding from Germany |

Pregnant: 28.9% unsure

Breastfeeding: 28.1% unsure |

Scientific data on the COVID-19 vaccination are too preliminary

Lack of enough information

Being anxious because of vaccine damage to the unborn or causing pregnancy Complications |

Solak et al, 202286 |

525 adults from Turkey |

- |

Need for cognitive closure |

| Sharma et al, 202187 |

428 African Americans from US |

48% were hesitant |

Perceived Advantages

Perceived Disadvantages

Participatory Dialogue

Behavior Confidence |

Spinewine et al, 202188 |

1132 HCWs from

Belgium |

37.1% were hesitant |

Concerns about side effects, rushed vaccine development, and effectiveness

Low perceived threat |

| Schwarzinger et al, 202189 |

1942 adults from France |

71.2% were hesitant |

Vaccine efficacy

Concerns about side effects

Communication about the collective benefits of herd immunity |

Stojanovic et al, 202117 |

32028 individuals from Brazil, Canada, Colombia, France, Italy, Turkey, UK, US |

27% were hesitant.

France had highest level of hesitancy (47.3%) and Brazil the lowest (9.6%) |

Fewer COVID-19 health concerns

Higher personal financial concerns |

| Theis et al, 202190 |

816 Wright-Patterson Air Force Base (WPAFB) from the US |

22.7% |

Concerns about side effects and effectiveness

Vaccines making them feel sick

Vaccine infects them COVID-19

Being worried about misinformation/political agenda |

West et al, 202191 |

360 Temporary Foreign Workers from Bangladesh |

25% were hesitant |

Fear of side effects

Low perceived threat

Willingness to take the vaccine by more people first

Lack of enough information |

| Ticona et al, 202192 |

985 individuals from Brazil |

26.1% were hesitant |

Concerns about effectiveness and side effects |

Wu et al, 202293 |

306 adult

from the US |

33.99% were hesitant |

Concerns about side effects, safety, ingredients, rushed vaccine development, and effectiveness

Low perceived threat

Concerns about vaccine causing MS relapse, making MS medication ineffective, and getting the COVID-19 infection

Prior bad experiences with other vaccines |

| Tram et al, 20213 |

459235 households from the US |

10.2% “probably NOT” get a vaccine |

Concern about side effects and safety

Other people need it more than I

Lack of trust in the vaccine

Lack of confidence in government |

Xu et al, 202194 |

4748 parents from China |

25.2% of women, 26.1% of their spouses, and 27.3% of their children |

Psychological distress

Concern about safety |

| Turhan et al, 202195 |

620 individuals from Turkey |

- |

Lack of trust in healthcare system |

Yanto et al, 202196 |

190 adults from Indonesia |

13.2% were hesitant |

Agreeableness trait

Neuroticism

Lack of confidence in government, scientists, and HCWs |

| Wang & Zhang 202197 |

382 parents from China |

- |

Psychological flexibility

Self-efficacy

Coping style |

Zhang et al, 202198 |

1015 individuals from China |

82 Doubtful 39 Strongly Hesitancy |

Conspiracy beliefs

Medical mistrust

Knowledge of vaccines

Vaccine confidence and complacency |

| Wang et al, 202199 |

7318 adults from China |

67.6% were hesitant |

Confidence

Complacent

Convenience |

- |

- |

- |

- |

HCWs: health care workers.

Risk of bias

On average the studies met 68.5% (range = 51-86%) of the rating criteria. On the whole, the studies showed a moderate risk of bias, and more than half of them (n = 63; 69%) were of good quality (range = 70 to 85).

Variations in vaccine hesitancy and refusal

Vaccination hesitation rate varied from 4% among patients with primary ciliary dyskinesia16 to 74.3% (mean = 29.72) in people over 18 years of age living in Kuwait20 and reported refusal rates were 8.6% to 75.5% (mean = 26.88). In addition to the hesitancy rate, some studies also measured uncertainty (mean = 23.25), undecided (mean = 29.4), and reluctance (mean = 24.15).

Cognitive Determinants of COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy

Among the evaluated peer-reviewed literature, based on a collective sample of 1 335 139 participants, several categories of cognitive determinants were extracted:

5C Psychological Antecedents

A number of studies have used in a way five factors of confidence, complacency, constraints, calculations, and collective responsibility, which are known as 5C psychological antecedents.3,5,6,8,9,14-16,20,21,24-36,38-44,46-63,65-77,79,80,82-84,88,89,91-93,94-98 Confidence and complacency in the vaccine were two of the most frequent variables used by most studies. We categorized the concerns about probable vaccine side effects, vaccine effectiveness, the rapid procedure of vaccine manufacturing, and lack of trust in the efficiency of some brands under the perceived confidence of participants about the COVID-19 vaccine. In addition, perceived threats, including perceived susceptibility and severity, the risk posed by COVID-19, and risk propensity, were categorized as complacency.

Perceived self-efficacy and perceived behavioral control

According to studies, individuals with higher general self-efficacy and specific self-efficacy of preventing COVID-19 displayed stronger intentions to get vaccinated.67,97 In addition, in relation to perceived behavioral control, Hossain et al found that the respondents who registered voluntarily for COVID-19 vaccination had been less vaccine-hesitant.6

Perceived locus of control

Murphy et al used the locus of control variable as a psychological indicator of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance/hesitancy/resistance.18 They measured internal and external locus of control among Irish and England participants. Their results indicated that in the Irish and UK, vaccine hesitant/resistant people felt more control over their lives, acted based on their preferences, and had higher levels of internal locus of control.

Inhibiting subjective norms

Social/peer influence was the variable that some studies applied as a predictor of COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy.6,49,67 The results of their studies have shown that vaccine hesitancy tended to decrease with the increase of perceived subjective norms.

Anti-vaccine beliefs

We found that conspiracy theories concerning the COVID-19 vaccine have a significant impact on decision to hesitate. For example, some related beliefs were as follows: (i) Vaccine protection against COVID-19 is temporary; (ii) COVID-19 vaccines modify DNA; iii) the vaccine can induce other disorders such as autism or autoimmune diseases; (iv) COVID-19’s vaccine has chips implanted to control people; (v) the vaccine’s efficacy and published studies are untrue37; (vi) The virus is manufactured by humans ; (vii) the virus’s spread is an deliberate attempt to reduce the global population’s growth; and viii) COVID-19 is a biological weapon produced by China to crush the West.50

Stress and anxiety

Perceived stress has been used as a factor associated with COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy by de Sousa et al in Portuguese-speaking countries. They found a significant direct relationship between vaccine hesitancy and perceived stress.37 According to Xu et al, parents with psychological distress are more likely to hesitate to vaccinate for themselves, their spouses, and their children.94 Feeling agitated, sad, or anxious were other factors that were shown to be associated with vaccine hesitancy in a survey conducted by Gomes et al.47

Fears and concerns

Some studies reported fears such as fear of needles and injection,30 fear of infecting significant others,41 and higher personal financial concerns/fear of the expensive vaccination costs, which make people hesitate to adopt the COVID-19 vaccination. Additionally, the Ghaffari-Rafi et al study showed that patients with an insight into a preexisting medical condition believed that COVID-19 vaccination might threaten their health because of existing disease.45

Optimism

Optimism indicates the extent to which people hold positive expectancies for their future100 used by Schernhammer et al. They explored the correlation of optimism with hesitancy toward COVID-19 and reported that persons with medium to high optimism were less prone to vaccine-hesitancy.78

Personality traits

Some personality traits such as personal anomie, altruism, conscientiousness, agreeableness, and neuroticism have been used by several studies9,18,96 as psychological indicators of vaccine hesitancy. These studies indicated that higher levels of neuroticism, perceptions of anomie, and lower levels of agreeableness, conscientiousness, and altruism might influence the increase in COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy.

Discussion

This systematic review aimed to investigate the cognitive determinants of COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy. We discuss several cognitive factors that may play a role in COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy.

Confidence and complacency, two antecedents of the 5C psychological model, were among the most common cognitive factors studied to explain COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. The confidence was relevant to trust in the government’s decisions, the effectiveness of the vaccines, and the COVID-19 Vaccine delivery system.101 Confidence in the COVID-19 vaccine and concerns about its safety have been reported in most studies.5,14,20,29,31,38 According to studies, concerns about the probable side effects of the vaccine, its ingredients, its effectiveness, and safety, as well as the rapid process of vaccine production and the vaccines approval process, reduce the trust of people in the COVID-19 vaccine. Although most of the side effects of COVID-19 vaccines have been confirmed scientifically, some are undocumented or have fewer shreds of evidence. This can lead to insufficient knowledge, the formation of improper beliefs, incorrect information, and mistrust in vaccines.102

When a vaccine is quickly produced and distributed, information sources such as the Internet and other social media disseminate claims about its harms and ineffectiveness.103,104 Much of this information may exaggerate risks associated with the COVID-19 vaccines105 and could cause the formation of anti-vaccine conspiracy beliefs.106,107 Most of the information that is published by unreliable sources targets the safety of vaccines, worries people about short-term adverse reactions and possible long-term effects of the COVID-19 vaccine, and can ultimately lead to hesitation and refusal to vaccinate.105

On the other hand, confidence in vaccines can result from people’s trust in the public health care system and in delivering safe and effective vaccines.101 In this regard, the WHO vaccine advisory group highlights the role of healthcare workers in building confidence in COVID-19 vaccines. Because healthcare providers can be effective in improving people’s insights and awareness about the benefits of vaccination and addressing people’s concerns about newly developed vaccines.108

The role of distrust of the government and health care system is significant in causing vaccine hesitancy.28,30,41,97 Usually, people are worried about the side effects of vaccines imported to the country or manufactured there, which may lead to a lack of trust and fear about vaccines. 7 The lower the people’s trust in the government, the more risk perception of the threat. Therefore, governments should provide safe vaccines.69 In fact, trust in the government and health authorities is essential for vaccine acceptance, especially in cases such as COVID-19, where anxiety about the nature of the disease is significant.101

When the nature of a disease is not completely clear, the chance of spreading conspiracy beliefs may increase, and it was recognized that in the COVID-19 pandemic, the growth of conspiracy beliefs and the reduction of people’s participation in vaccination have occurred.9 Conspiracy theories explain the negative emotions and uncertainty that traditionally increase during times of social crisis (such as war, environmental disaster, and terrorism). In this situation, uncertainty, powerlessness, and fear and anxiety increase.9 With the rapid prevalence of the COVID-19 pandemic, a wide range of conspiracy beliefs emerged and spread. For example, COVID-19 is a hoax, a biological weapon developed by the Chinese, and the COVID-19 vaccine microchips will be injected to control COVID-19,9,109 which indicates that the vaccine manufacturing companies underestimate the side effects of the vaccines.9 The development of such beliefs may cause mistrust and reduce the vaccination acceptance rate. Therefore, delivering information that focuses on the effectiveness and safety of the COVID-19 vaccine from reliable sources can be influential in reducing vaccination hesitancy.

The second antecedent of 5c psychological is complacency. More complacency is defined as a lower perceived threat of disease and the belief that vaccination is unnecessary as a preventive measure. In other words, people with high complacency have more feelings of invulnerability and less preventive behavior than those with low complacency.101 According to the Health Belief Model (HBM), people are most likely to take a preventative behavior when they perceive the threat of disease. The HBM is one of the most widely used models to explain vaccination behavior.6,110 Studies have shown that worrying about getting infected with COVID-19 and believing in the seriousness of its consequences can persuade people to get the COVID-19 vaccine.6,111 Also, the newer fourth-generation models, such as the multi-theory model of health behavior change, have underscored the role of getting convinced of the advantages of behavior change over the disadvantages and building behavioral confidence.87

One of the important factors in getting the vaccine is the perceived benefits of a vaccine. Such as the belief in its protective effect against COVID-19 and its subsequent side effects are among the influential factors in adherence to the COVID-19 vaccine.111 In contradiction of that, perceived physical and psychological barriers that can make the vaccine an unpleasant experience 21,111 and concerns about safety and its probable side effects, fear of needles, and its costs can increase vaccination hesitancy.112,113

Locus of control and belief in chance were other cognitive factors recognized in this study. Health locus of control refers to the degree to which a person believes that he/she, as opposed to external forces, has control over his/her health. Locus of control is conceptualized as internal or external.114 The internal dimension is positively associated with engaging in health behaviors, and chance as the external dimension is positively related to non-adherence to health behaviors.115 People whose health locus of control is external may be doubtful about how to behave in a healthy manner,116 such as vaccination, and it is reported that the external locus of health control is related to a lower level of childhood vaccination through parental attitudes.

Studies have used self-efficacy and perceived behavioral control as predictors of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy.6,67,97 As self-efficacy reflects one’s belief in their ability to perform a particular behavior,110 like the COVID-19 vaccination, perceived behavioral control similar to self-efficacy also refers to the person’s belief that the considered behavior is under control. As a result, most psychosocial health behavior theories postulated that self-efficacy and perceived behavioral control had been introduced as major determinants of engaging in health behavior.110 Also, the role of behavioral confidence has been underscored in the newer fourth-generation models, such as the multi-theory model (MTM) of health behavior change.

Limitations

Due to resource constraints needed to translate and retranslate studies published in other languages, the investigation was limited to manuscripts published in English only. Hence the results are not representative of research published in other languages. Further, the search in this review was limited to the title, keywords, and abstract of each publication. Perhaps more in-depth search could have resulted in identification of more studies. A single statistical analysis of the data was not practical or feasible because of the sizable variability in the cognitive determinants of COVID-19 across studies. Therefore, a narrative analysis was accomplished, thereby limiting the external validity of the conclusions.

Implications for practice and future research

Given that hesitancy and distrust of a new health product and service such as the COVID-19, vaccine will always exist, the development of strategies that can build trust in people to vaccinate and improve the government’s ability to manage and successfully implement mass vaccination calls for attention. According to studies, several factors can contribute to building trust117:

Responsiveness: Health authorities should show competence in responding to people’s health needs, fears, and concerns by establishing a transparent and coherent relationship about the vaccine quality. Qualitative research can help identify people’s needs, concerns, and fears about the COVID-19 vaccination.

Openness: The public must understand the importance of rapid vaccine production and distribution to achieve herd immunity during new epidemics. Also, more importantly, people should ensure that no quality or safety standards have been sacrificed for speed in the vaccine production process. Therefore, people should be informed about all phases of production, approval, evaluation, and distribution of vaccination through a proper communication strategy. Paying attention to myths, misconceptions, and false information about vaccination, monitoring the messages of widely used social media such as the Internet, spreading correct information through the creation and introduction of reliable information sources, and increasing health literacy and e-health literacy of people are other strategies for considering openness.

Reliability, integrity, and fairness: Holding campaigns to encourage people to take the vaccine with the presence of health authorities, pioneering them in receiving the vaccine, and providing information about all the benefits and harms of the vaccine, will increase confidence in the vaccination.

Conclusion

COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy as a significant challenge for public health has been reported in many countries. Our findings highlight the importance of understanding the cognitive factors contributing to COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy to develop effective health communication programs for persuading people toward COVID-19 vaccination and the most common reason for vaccine hesitancy was a lack of confidence and complacency. Multiple factors, including concerns about vaccine safety and side effects, perceived susceptibility and severity, the risk posed by COVID-19, and risk propensity, could influence delay or refusal to accept the vaccine. Information through trusted sources to reduce hesitancy about the COVID-19 vaccination.

Competing Interests

Hamid Alahverdipour is Editor-in-Chief of the Health Promotion Perspectives. Other authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical Approval

This research was performed based on Tabriz University of Medical Sciences ethics committee approval (Approval ID: IR.TBZMED.REC.1400.564).

Funding

This study was supported by Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, the decision to publish, or the preparation of the manuscript.

Supplementary Files

Supplementary file 1 contains search strategy applied to the PubMed database.

(pdf)

References

- Alqudeimat Y, Alenezi D, AlHajri B, Alfouzan H, Almokhaizeem Z, Altamimi S. Acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine and its related determinants among the general adult population in Kuwait. Med Princ Pract 2021; 30(3):262-71. doi: 10.1159/000514636 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Adebisi YA, Alaran AJ, Bolarinwa OA, Akande-Sholabi W, Lucero-Prisno DE. When it is available, will we take it? Social media users’ perception of hypothetical COVID-19 vaccine in Nigeria. Pan Afr Med J 2021; 38:230. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2021.38.230.27325 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Tram KH, Saeed S, Bradley C, Fox B, Eshun-Wilson I, Mody A. Deliberation, dissent, and distrust: understanding distinct drivers of coronavirus disease 2019 vaccine hesitancy in the United States. Clin Infect Dis 2022; 74(8):1429-41. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab633 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Caserotti M, Girardi P, Rubaltelli E, Tasso A, Lotto L, Gavaruzzi T. Associations of COVID-19 risk perception with vaccine hesitancy over time for Italian residents. Soc Sci Med 2021; 272:113688. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.113688 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Costantino A, Topa M, Roncoroni L, Doneda L, Lombardo V, Stocco D. COVID-19 vaccine: a survey of hesitancy in patients with celiac disease. Vaccines (Basel) 2021; 9(5):511. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9050511 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Hossain MB, Alam MZ, Islam MS, Sultan S, Faysal MM, Rima S. Health belief model, theory of planned behavior, or psychological antecedents: what predicts COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy better among the Bangladeshi adults?. Front Public Health 2021; 9:711066. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.711066 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Dinga JN, Sinda LK, Titanji VPK. Assessment of vaccine hesitancy to a COVID-19 vaccine in Cameroonian adults and its global implication. Vaccines (Basel) 2021; 9(2):175. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9020175 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- López-Cepero A, Cameron S, Negrón LE, Colón-López V, Colón-Ramos U, Mattei J. Uncertainty and unwillingness to receive a COVID-19 vaccine in adults residing in Puerto Rico: assessment of perceptions, attitudes, and behaviors. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2021; 17(10):3441-9. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2021.1938921 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- McCarthy M, Murphy K, Sargeant E, Williamson H. Examining the relationship between conspiracy theories and COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy: a mediating role for perceived health threats, trust, and anomie?. Anal Soc Issues Public Policy 2022; 22(1):106-29. doi: 10.1111/asap.12291 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev 2015; 4(1):1. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- McGowan J, Sampson M, Salzwedel DM, Cogo E, Foerster V, Lefebvre C. PRESS peer review of electronic search strategies: 2015 guideline statement. J Clin Epidemiol 2016; 75:40-6. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.01.021 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Int J Surg 2014; 12(12):1495-9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.07.013 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Limaye D, Limaye V, Pitani RS, Fortwengel G, Sydymanov A, Otzipka C. Development of a quantitative scoring method for STROBE checklist. Acta Pol Pharm 2018; 75(5):1095-106. doi: 10.32383/appdr/84804 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Blanchi S, Torreggiani M, Chatrenet A, Fois A, Mazé B, Njandjo L. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in patients on dialysis in Italy and France. Kidney Int Rep 2021; 6(11):2763-74. doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2021.08.030 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Gerretsen P, Kim J, Caravaggio F, Quilty L, Sanches M, Wells S. Individual determinants of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. PLoS One 2021; 16(11):e0258462. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0258462 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Pedersen ESL, Mallet MC, Lam YT, Bellu S, Cizeau I, Copeland F. COVID-19 vaccinations: perceptions and behaviours in people with primary ciliary dyskinesia. Vaccines (Basel) 2021; 9(12):1496. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9121496 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Stojanovic J, Boucher VG, Gagne M, Gupta S, Joyal-Desmarais K, Paduano S. Global trends and correlates of COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy: findings from the iCARE study. Vaccines (Basel) 2021; 9(6):661. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9060661 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Murphy J, Vallières F, Bentall RP, Shevlin M, McBride O, Hartman TK. Psychological characteristics associated with COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and resistance in Ireland and the United Kingdom. Nat Commun 2021; 12(1):29. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-20226-9 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Kuhn R, Henwood B, Lawton A, Kleva M, Murali K, King C. COVID-19 vaccine access and attitudes among people experiencing homelessness from pilot mobile phone survey in Los Angeles, CA. PLoS One 2021; 16(7):e0255246. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0255246 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Al-Ayyadhi N, Ramadan MM, Al-Tayar E, Al-Mathkouri R, Al-Awadhi S. Determinants of hesitancy towards COVID-19 vaccines in State of Kuwait: an exploratory internet-based survey. Risk Manag Healthc Policy 2021; 14:4967-81. doi: 10.2147/rmhp.s338520 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Abedin M, Islam MA, Rahman FN, Reza HM, Hossain MZ, Hossain MA. Willingness to vaccinate against COVID-19 among Bangladeshi adults: understanding the strategies to optimize vaccination coverage. PLoS One 2021; 16(4):e0250495. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0250495 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Al-Sanafi M, Sallam M. Psychological determinants of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among healthcare workers in Kuwait: a cross-sectional study using the 5C and vaccine conspiracy beliefs scales. Vaccines (Basel) 2021; 9(7):701. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9070701 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Adane M, Ademas A, Kloos H. Knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions of COVID-19 vaccine and refusal to receive COVID-19 vaccine among healthcare workers in northeastern Ethiopia. BMC Public Health 2022; 22(1):128. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-12362-8 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Al-Mistarehi AH, Kheirallah KA, Yassin A, Alomari S, Aledrisi MK, Bani Ata EM. Determinants of the willingness of the general population to get vaccinated against COVID-19 in a developing country. Clin Exp Vaccine Res 2021; 10(2):171-82. doi: 10.7774/cevr.2021.10.2.171 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Adigwe OP. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and willingness to pay: emergent factors from a cross-sectional study in Nigeria. Vaccine X 2021; 9:100112. doi: 10.1016/j.jvacx.2021.100112 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Alrajeh AM, Daghash H, Buanz SF, Altharman HA, Belal S. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among the adult population in Saudi Arabia. Cureus 2021; 13(12):e20197. doi: 10.7759/cureus.20197 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Aemro A, Amare NS, Shetie B, Chekol B, Wassie M. Determinants of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among health care workers in Amhara region referral hospitals, Northwest Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Epidemiol Infect 2021; 149:e225. doi: 10.1017/s0950268821002259 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Alzubaidi H, Samorinha C, Saddik B, Saidawi W, Abduelkarem AR, Abu-Gharbieh E. A mixed-methods study to assess COVID-19 vaccination acceptability among university students in the United Arab Emirates. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2021; 17(11):4074-82. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2021.1969854 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Afzal A, Shariff MA, Perez-Gutierrez V, Khalid A, Pili C, Pillai A. Impact of local and demographic factors on early COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among health care workers in New York City public hospitals. Vaccines (Basel) 2022; 10(2):273. doi: 10.3390/vaccines10020273 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Le An P, Nguyen HTN, Nguyen DD, Vo LY, Huynh G. The intention to get a COVID-19 vaccine among the students of health science in Vietnam. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2021; 17(12):4823-8. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2021.1981726 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Aguilar Ticona JP, Nery N Jr, Victoriano R, Fofana MO, Ribeiro GS, Giorgi E. Willingness to get the COVID-19 vaccine among residents of slum settlements. Vaccines (Basel) 2021; 9(9):951. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9090951 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ashok N, Krishnamurthy K, Singh K, Rahman S, Majumder MAA. High COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among healthcare workers: should such a trend require closer attention by policymakers?. Cureus 2021; 13(9):e17990. doi: 10.7759/cureus.17990 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Badr H, Zhang X, Oluyomi A, Woodard LD, Adepoju OE, Raza SA. Overcoming COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy: insights from an online population-based survey in the United States. Vaccines (Basel) 2021; 9(10):1100. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9101100 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Baccolini V, Renzi E, Isonne C, Migliara G, Massimi A, De Vito C. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among Italian university students: a cross-sectional survey during the first months of the vaccination campaign. Vaccines (Basel) 2021; 9(11):1292. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9111292 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Chaudhary FA, Ahmad B, Khalid MD, Fazal A, Javaid MM, Butt DQ. Factors influencing COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and acceptance among the Pakistani population. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2021; 17(10):3365-70. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2021.1944743 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Bălan A, Bejan I, Bonciu S, Eni CE, Ruță S. Romanian medical students’ attitude towards and perceived knowledge on COVID-19 vaccination. Vaccines (Basel) 2021; 9(8):854. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9080854 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- de Sousa Á FL, Teixeira JRB, Lua I, de Oliveira Souza F, Ferreira AJF, Schneider G. Determinants of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in Portuguese-speaking countries: a structural equations modeling approach. Vaccines (Basel) 2021; 9(10):1167. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9101167 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Bolatov AK, Seisembekov TZ, Askarova AZ, Pavalkis D. Barriers to COVID-19 vaccination among medical students in Kazakhstan: development, validation, and use of a new COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy Scale. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2021; 17(12):4982-92. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2021.1982280 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Du M, Tao L, Liu J. The association between risk perception and COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy for children among reproductive women in China: an online survey. Front Med (Lausanne) 2021; 8:741298. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.741298 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Bou Hamdan M, Singh S, Polavarapu M, Jordan TR, Melhem NM. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among university students in Lebanon. Epidemiol Infect 2021; 149:e242. doi: 10.1017/s0950268821002314 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ebrahimi OV, Johnson MS, Ebling S, Amundsen OM, Halsøy Ø, Hoffart A. Risk, trust, and flawed assumptions: vaccine hesitancy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Public Health 2021; 9:700213. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.700213 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Butter S, McGlinchey E, Berry E, Armour C. Psychological, social, and situational factors associated with COVID-19 vaccination intentions: a study of UK key workers and non-key workers. Br J Health Psychol 2022; 27(1):13-29. doi: 10.1111/bjhp.12530 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ehde DM, Roberts MK, Humbert AT, Herring TE, Alschuler KN. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in adults with multiple sclerosis in the United States: a follow up survey during the initial vaccine rollout in 2021. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2021; 54:103163. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2021.103163 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- El-Sokkary RH, El Seifi OS, Hassan HM, Mortada EM, Hashem MK, Gadelrab M. Predictors of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among Egyptian healthcare workers: a cross-sectional study. BMC Infect Dis 2021; 21(1):762. doi: 10.1186/s12879-021-06392-1 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ghaffari-Rafi A, Teehera KB, Higashihara TJ, Morden FTC, Goo C, Pang M. Variables associated with coronavirus disease 2019 vaccine hesitancy amongst patients with neurological disorders. Infect Dis Rep 2021; 13(3):763-810. doi: 10.3390/idr13030072 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Fares S, Elmnyer MM, Mohamed SS, Elsayed R. COVID-19 vaccination perception and attitude among healthcare workers in Egypt. J Prim Care Community Health 2021; 12:21501327211013303. doi: 10.1177/21501327211013303 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Gomes IA, Soares P, Rocha JV, Gama A, Laires PA, Moniz M. Factors associated with COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy after implementation of a mass vaccination campaign. Vaccines (Basel) 2022; 10(2):281. doi: 10.3390/vaccines10020281 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Fedele F, Aria M, Esposito V, Micillo M, Cecere G, Spano M. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy: a survey in a population highly compliant to common vaccinations. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2021; 17(10):3348-54. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2021.1928460 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Griva K, Tan KYK, Chan FHF, Periakaruppan R, Ong BWL, Soh ASE. Evaluating rates and determinants of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy for adults and children in the Singapore population: strengthening our community’s resilience against threats from emerging infections (SOCRATEs) cohort. Vaccines (Basel) 2021; 9(12):1415. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9121415 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Freeman D, Loe BS, Chadwick A, Vaccari C, Waite F, Rosebrock L. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in the UK: the Oxford coronavirus explanations, attitudes, and narratives survey (Oceans) II. Psychol Med 2022; 52(14):3127-41. doi: 10.1017/s0033291720005188 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Hwang SE, Kim WH, Heo J. Socio-demographic, psychological, and experiential predictors of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in South Korea, October-December 2020. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2022; 18(1):1-8. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2021.1983389 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Genovese C, Costantino C, Odone A, Trimarchi G, La Fauci V, Mazzitelli F. A knowledge, attitude, and perception study on flu and COVID-19 vaccination during the COVID-19 pandemic: multicentric Italian survey insights. Vaccines (Basel) 2022; 10(2):142. doi: 10.3390/vaccines10020142 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Hossain E, Rana J, Islam S, Khan A, Chakrobortty S, Ema NS. COVID-19 vaccine-taking hesitancy among Bangladeshi people: knowledge, perceptions and attitude perspective. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2021; 17(11):4028-37. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2021.1968215 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Jain J, Saurabh S, Kumar P, Verma MK, Goel AD, Gupta MK. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among medical students in India. Epidemiol Infect 2021; 149:e132. doi: 10.1017/s0950268821001205 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Li M, Zheng Y, Luo Y, Ren J, Jiang L, Tang J. Hesitancy toward COVID-19 vaccines among medical students in Southwest China: a cross-sectional study. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2021; 17(11):4021-7. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2021.1957648 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Kanyike AM, Olum R, Kajjimu J, Ojilong D, Akech GM, Nassozi DR. Acceptance of the coronavirus disease-2019 vaccine among medical students in Uganda. Trop Med Health 2021; 49(1):37. doi: 10.1186/s41182-021-00331-1 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Liddell BJ, Murphy S, Mau V, Bryant R, O’Donnell M, McMahon T. Factors associated with COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy amongst refugees in Australia. Eur J Psychotraumatol 2021; 12(1):1997173. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2021.1997173 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Khairat S, Zou B, Adler-Milstein J. Factors and reasons associated with low COVID-19 vaccine uptake among highly hesitant communities in the US. Am J Infect Control 2022; 50(3):262-7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2021.12.013 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Knight H, Jia R, Ayling K, Bradbury K, Baker K, Chalder T. Understanding and addressing vaccine hesitancy in the context of COVID-19: development of a digital intervention. Public Health 2021; 201:98-107. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2021.10.006 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Luk TT, Zhao S, Wu Y, Wong JY, Wang MP, Lam TH. Prevalence and determinants of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine hesitancy in Hong Kong: a population-based survey. Vaccine 2021; 39(27):3602-7. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.05.036 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Kuçukkarapınar M, Karadag F, Budakoglu I, Aslan S, Ucar O, Yay A. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and its relationship with illness risk perceptions, affect, worry, and public trust: an online serial cross-sectional survey from Turkey. Psychiatr Clin Psychopharmacol 2021; 31(1):98-109. doi: 10.5152/pcp.2021.21017 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Marijanović I, Kraljević M, Buhovac T, Sokolović E. Acceptance of COVID-19 vaccination and its associated factors among cancer patients attending the oncology clinic of University Clinical Hospital Mostar, Bosnia and Herzegovina: a cross-sectional study. Med Sci Monit 2021; 27:e932788. doi: 10.12659/msm.932788 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Lee M, You M. Direct and indirect associations of media use with COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in South Korea: cross-sectional web-based survey. J Med Internet Res 2022; 24(1):e32329. doi: 10.2196/32329 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Moujaess E, Zeid NB, Samaha R, Sawan J, Kourie H, Labaki C. Perceptions of the COVID-19 vaccine among patients with cancer: a single-institution survey. Future Oncol 2021; 17(31):4071-9. doi: 10.2217/fon-2021-0265 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Muhajarine N, Adeyinka DA, McCutcheon J, Green KL, Fahlman M, Kallio N. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and refusal and associated factors in an adult population in Saskatchewan, Canada: evidence from predictive modelling. PLoS One 2021; 16(11):e0259513. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0259513 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Orangi S, Pinchoff J, Mwanga D, Abuya T, Hamaluba M, Warimwe G. Assessing the level and determinants of COVID-19 vaccine confidence in Kenya. Vaccines (Basel) 2021; 9(8):936. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9080936 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Patwary MM, Bardhan M, Disha AS, Hasan M, Haque MZ, Sultana R. Determinants of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among the adult population of Bangladesh using the health belief model and the theory of planned behavior model. Vaccines (Basel) 2021; 9(12):1393. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9121393 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Navarre C, Roy P, Ledochowski S, Fabre M, Esparcieux A, Issartel B. Determinants of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in French hospitals. Infect Dis Now 2021; 51(8):647-53. doi: 10.1016/j.idnow.2021.08.004 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Park HK, Ham JH, Jang DH, Lee JY, Jang WM. Political ideologies, government trust, and COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in South Korea: a cross-sectional survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021; 18(20):10655. doi: 10.3390/ijerph182010655 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Nazlı ŞB, Yığman F, Sevindik M, Deniz Özturan D. Psychological factors affecting COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. Ir J Med Sci 2022; 191(1):71-80. doi: 10.1007/s11845-021-02640-0 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Paschoalotto MAC, Costa E, de Almeida SV, Cima J, da Costa JG, Santos JV. Running away from the jab: factors associated with COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in Brazil. Rev Saude Publica 2021; 55:97. doi: 10.11606/s1518-8787.2021055003903 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Nery N Jr, Ticona JPA, Cardoso CW, Prates A, Vieira HCA, Salvador de Almeida A. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and associated factors according to sex: a population-based survey in Salvador, Brazil. PLoS One 2022; 17(1):e0262649. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0262649 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Nguyen LH, Hoang MT, Nguyen LD, Ninh LT, Nguyen HTT, Nguyen AD. Acceptance and willingness to pay for COVID-19 vaccines among pregnant women in Vietnam. Trop Med Int Health 2021; 26(10):1303-13. doi: 10.1111/tmi.13666 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Peirolo A, Posfay-Barbe KM, Rohner D, Wagner N, Blanchard-Rohner G. Acceptability of COVID-19 vaccine among hospital employees in the Department of Paediatrics, Gynaecology and Obstetrics in the university hospitals of Geneva, Switzerland. Front Public Health 2021; 9:781562. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.781562 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Okubo R, Yoshioka T, Ohfuji S, Matsuo T, Tabuchi T. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and its associated factors in Japan. Vaccines (Basel) 2021; 9(6):662. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9060662 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Prickett KC, Habibi H, Carr PA. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and acceptance in a cohort of diverse New Zealanders. Lancet Reg Health West Pac 2021; 14:100241. doi: 10.1016/j.lanwpc.2021.100241 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Rahman MM, Chisty MA, Sakib MS, Abdul Quader M, Shobuj IA, Alam MA. Status and perception toward the COVID-19 vaccine: a cross-sectional online survey among adult population of Bangladesh. Health Sci Rep 2021; 4(4):e451. doi: 10.1002/hsr2.451 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Schernhammer E, Weitzer J, Laubichler MD, Birmann BM, Bertau M, Zenk L. Correlates of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in Austria: trust and the government. J Public Health (Oxf) 2022; 44(1):e106-e16. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdab122 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Reno C, Maietti E, Fantini MP, Savoia E, Manzoli L, Montalti M. Enhancing COVID-19 vaccines acceptance: results from a survey on vaccine hesitancy in Northern Italy. Vaccines (Basel) 2021; 9(4):378. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9040378 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Shekhar R, Sheikh AB, Upadhyay S, Singh M, Kottewar S, Mir H. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among health care workers in the United States. Vaccines (Basel) 2021; 9(2):119. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9020119 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Roberts HA, Clark DA, Kalina C, Sherman C, Brislin S, Heitzeg MM. To vax or not to vax: predictors of anti-vax attitudes and COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy prior to widespread vaccine availability. PLoS One 2022; 17(2):e0264019. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0264019 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Shen X, Dong H, Feng J, Jiang H, Dowling R, Lu Z. Assessing the COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in the Chinese adults using a generalized vaccine hesitancy survey instrument. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2021; 17(11):4005-12. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2021.1953343 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ruggiero KM, Wong J, Sweeney CF, Avola A, Auger A, Macaluso M. Parents’ intentions to vaccinate their children against COVID-19. J Pediatr Health Care 2021; 35(5):509-17. doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2021.04.005 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Soares P, Rocha JV, Moniz M, Gama A, Laires PA, Pedro AR. Factors associated with COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. Vaccines (Basel) 2021; 9(3):300. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9030300 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Schaal NK, Zöllkau J, Hepp P, Fehm T, Hagenbeck C. Pregnant and breastfeeding women’s attitudes and fears regarding the COVID-19 vaccination. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2022; 306(2):365-72. doi: 10.1007/s00404-021-06297-z [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Solak Ç, Peker-Dural H, Karlıdağ S, Peker M. Linking the behavioral immune system to COVID-19 vaccination intention: the mediating role of the need for cognitive closure and vaccine hesitancy. Pers Individ Dif 2022; 185:111245. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2021.111245 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Sharma M, Batra K, Batra R. A theory-based analysis of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among African Americans in the United States: a recent evidence. Healthcare (Basel) 2021; 9(10):1273. doi: 10.3390/healthcare9101273 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Spinewine A, Pétein C, Evrard P, Vastrade C, Laurent C, Delaere B. Attitudes towards COVID-19 vaccination among hospital staff-understanding what matters to hesitant people. Vaccines (Basel) 2021; 9(5):469. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9050469 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Schwarzinger M, Watson V, Arwidson P, Alla F, Luchini S. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in a representative working-age population in France: a survey experiment based on vaccine characteristics. Lancet Public Health 2021; 6(4):e210-e21. doi: 10.1016/s2468-2667(21)00012-8 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Theis SR, Li PC, Kelly D, Ocampo T, Berglund A, Morgan D. Perceptions and concerns regarding COVID-19 vaccination in a military base population. Mil Med 2022; 187(11-12):e1255-e60. doi: 10.1093/milmed/usab230 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- West H, Lawton A, Hossain S, Mustafa A, Razzaque A, Kuhn R. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among temporary foreign workers from Bangladesh. Health Syst Reform 2021; 7(1):e1991550. doi: 10.1080/23288604.2021.1991550 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Aguilar Ticona JP, Nery N Jr, Victoriano R, Fofana MO, Ribeiro GS, Giorgi E. Willingness to get the COVID-19 vaccine among residents of slum settlements. Vaccines (Basel) 2021; 9(9):951. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9090951 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Wu H, Ward M, Brown A, Blackwell E, Umer A. COVID-19 vaccine intent in Appalachian patients with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2022; 57:103450. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2021.103450 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, Zhang R, Zhou Z, Fan J, Liang J, Cai L. Parental psychological distress and attitudes towards COVID-19 vaccination: a cross-sectional survey in Shenzhen, China. J Affect Disord 2021; 292:552-8. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.06.003 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Turhan Z, Dilcen HY, Dolu İ. The mediating role of health literacy on the relationship between health care system distrust and vaccine hesitancy during COVID-19 pandemic. Curr Psychol 2022; 41(11):8147-56. doi: 10.1007/s12144-021-02105-8 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Yanto TA, Octavius GS, Heriyanto RS, Ienawi C, Nisa H, Pasai HE. Psychological factors affecting COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in Indonesia. Egypt J Neurol Psychiatr Neurosurg 2021; 57(1):177. doi: 10.1186/s41983-021-00436-8 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Zhang X. Influence of parental psychological flexibility on pediatric COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy: mediating role of self-efficacy and coping style. Front Psychol 2021; 12:783401. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.783401 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Guo Y, Zhou Q, Tan Z, Cao J. The mediating roles of medical mistrust, knowledge, confidence and complacency of vaccines in the pathways from conspiracy beliefs to vaccine hesitancy. Vaccines (Basel) 2021; 9(11):1342. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9111342 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Zhang Y, Long S, Fu X, Zhang X, Zhao S. Non-EPI vaccine hesitancy among Chinese adults: a cross-sectional study. Vaccines (Basel) 2021; 9(7):772. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9070772 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, Scheier MF, Segerstrom SC. Optimism. Clin Psychol Rev 2010; 30(7):879-89. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.01.006 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Burke PF, Masters D, Massey G. Enablers and barriers to COVID-19 vaccine uptake: an international study of perceptions and intentions. Vaccine 2021; 39(36):5116-28. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.07.056 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Betsch C, Bach Habersaat K, Deshevoi S, Heinemeier D, Briko N, Kostenko N. Sample study protocol for adapting and translating the 5C scale to assess the psychological antecedents of vaccination. BMJ Open 2020; 10(3):e034869. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-034869 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Salmon DA, Dudley MZ, Glanz JM, Omer SB. Vaccine hesitancy: causes, consequences, and a call to action. Vaccine 2015; 33 Suppl 4:D66-71. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.09.035 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Dubé E, Vivion M, MacDonald NE. Vaccine hesitancy, vaccine refusal and the anti-vaccine movement: influence, impact and implications. Expert Rev Vaccines 2015; 14(1):99-117. doi: 10.1586/14760584.2015.964212 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- McKee C, Bohannon K. Exploring the reasons behind parental refusal of vaccines. J Pediatr Pharmacol Ther 2016; 21(2):104-9. doi: 10.5863/1551-6776-21.2.104 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Jolley D, Douglas KM. The effects of anti-vaccine conspiracy theories on vaccination intentions. PLoS One 2014; 9(2):e89177. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089177 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Shapiro GK, Holding A, Perez S, Amsel R, Rosberger Z. Validation of the vaccine conspiracy beliefs scale. Papillomavirus Res 2016; 2:167-72. doi: 10.1016/j.pvr.2016.09.001 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Kwok KO, Li KK, Wei WI, Tang A, Wong SYS, Lee SS. Influenza vaccine uptake, COVID-19 vaccination intention and vaccine hesitancy among nurses: a survey. Int J Nurs Stud 2021; 114:103854. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.103854 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Lee SK, Sun J, Jang S, Connelly S. Misinformation of COVID-19 vaccines and vaccine hesitancy. Sci Rep 2022; 12(1):13681. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-17430-6 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K. . Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice 2008.

- Al-Metwali BZ, Al-Jumaili AA, Al-Alag ZA, Sorofman B. Exploring the acceptance of COVID-19 vaccine among healthcare workers and general population using health belief model. J Eval Clin Pract 2021; 27(5):1112-22. doi: 10.1111/jep.13581 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Lin Y, Hu Z, Zhao Q, Alias H, Danaee M, Wong LP. Understanding COVID-19 vaccine demand and hesitancy: a nationwide online survey in China. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2020; 14(12):e0008961. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0008961 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Guidry JPD, Laestadius LI, Vraga EK, Miller CA, Perrin PB, Burton CW. Willingness to get the COVID-19 vaccine with and without emergency use authorization. Am J Infect Control 2021; 49(2):137-42. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2020.11.018 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]