Health Promotion Perspectives. 13(4):254-266.

doi: 10.34172/hpp.2023.31

Systematic Review

Prevalence of physical activity counseling in primary care: A systematic review and meta-analysis

Apichai Wattanapisit Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Validation, 1, 2

Sarawut Lapmanee Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Validation, 3, *

Sirawee Chaovalit Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, 4

Charupa Lektip Conceptualization, Investigation, Validation, 5

Palang Chotsiri Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Software, 6

Author information:

1Department of Clinical Medicine, School of Medicine, Walailak University, Nakhon Si Thammarat, Thailand

2Family Medicine Clinic, Walailak University Hospital, Nakhon Si Thammarat, Thailand

3Department of Basic Medical Sciences, Faculty of Medicine, Siam University, Bangkok, Thailand

4Department of Physical Therapy, Faculty of Medicine, Prince of Songkla University, Songkhla, Thailand

5Department of Physical Therapy, School of Allied Health Sciences, Walailak University, Nakhon Si Thammarat, Thailand

6Department of Clinical Pharmacology, Mahidol-Oxford Tropical Medicine Research Unit, Faculty of Tropical Medicine, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand

Abstract

Background:

This systematic review aimed to summarize and evaluate the prevalence of physical activity (PA) counseling in primary care.

Methods:

Five databases (CINAHL Complete, Embase, Medline, PsycInfo, and Web of Science) were searched. Primary epidemiological studies on PA counseling in primary care were included. The Joanna Briggs Institute critical appraisal checklist for studies reporting prevalence data was used to assess the quality of studies. The review protocol was registered with PROSPERO (CRD42021284570).

Results:

After duplicate removal, 4990 articles were screened, and 120 full-text articles were then assessed. Forty studies were included, with quality assessment scores ranging from 5/9 to 9/9. The pooled prevalence of PA counseling based on 35 studies (199830 participants) was 37.9% (95% CI 31.2 to 44.6). The subgroup analyses showed that the prevalence of PA counseling was 33.1% (95% CI: 22.6 to 43.7) in females (10 studies), 32.1% (95% CI: 22.6 to 41.7) in males (10 studies), 65.5% (95% CI: 5.70 to 74.1) in people with diabetes mellitus (6 studies), 41.6% (95% CI: 34.9 to 48.3) in people with hypertension (5 studies), and 56.8% (95% CI: 31.7 to 82.0) in people with overweight or obesity (5 studies). All meta-analyses showed high levels of heterogeneity (I2=93% to 100%).

Conclusion:

The overall prevalence of PA counseling in primary care was low. The high levels of heterogeneity suggest variability in the perspectives and practices of PA counseling in primary care. PA counseling should be standardized to ensure its optimum effectiveness in primary care.

Keywords: Counseling, Exercise, Meta-analysis, Prevalence, Primary health care

Copyright and License Information

© 2023 The Author(s).

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Funding Statement

There was no funding for this work.

Introduction

Physical activity (PA) counseling is an effective approach to increase PA levels among patients in primary care.1-3 The current World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines on PA recommend that people with chronic medical conditions should participate in at least 150–300 min/wk of moderate-intensity aerobic PA or at least 75–150 min/wk of vigorous-intensity aerobic PA or an equivalent combination, as well as at least 2 times/week muscle-strengthening and at least 3 times/week of multicomponent activities.4 Meeting the recommended levels of PA decreases the risk of major non-communicable diseases and premature death.5-8

Practices and characteristics of PA counseling vary among different settings.9-11 A variety of models (e.g., transtheoretical model) and theories (e.g., social cognitive theory) have been applied to understand the mechanisms of PA behaviors.12-14 In addition, several programs for promoting PA have been implemented, such as Exercise is Medicine (in the USA, Canada, Australia, Poland, Singapore) and Green Prescription (in New Zealand).10These programs help primary care providers to provide PA counseling.

A systematic review by Orrow et al revealed that promoting PA in 12 patients may prompt one patient to become more active.15 This highlights the importance of improving the prevalence of PA counseling in primary care. However, epidemiological studies report a wide range of prevalence of PA counseling in various settings.16,17 This limits the understanding of prevalence of PA counseling in primary care at the global level.

This systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to summarize and evaluate the prevalence of PA counseling in primary care across various settings worldwide. In addition, the subgroup analyses aimed to calculate the pooled prevalence of PA counseling by sex and medical condition. Determining the current prevalence of PA counseling can help to understand current practices and set realistic goals to increase the prevalence.

Materials and Methods

The systematic review protocol was prospectively developed and registered with PROSPERO (registration number: CRD42021284570). This systematic review follows the reporting guidelines of the 2020 Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement.18,19

Information sources and search strategy

Five databases, comprising CINAHL Complete, Embase, Medline (via the PubMed interface), PsycInfo, and Web of Science, were searched from database inception to 28th November 2021. The updated search was performed at the time of manuscript revision (the updated search covered articles published between 28th November 2021 and 28th August 2023). The search strategy was based on the PICO mnemonic, which included population (any), intervention (physical activity counseling in primary care), comparison (none), and outcome (prevalence), as applicable. All the authors reviewed and finalized the search terms, which were adapted for each database (Supplementary file 1, Table S1). A filter was applied to obtain only English articles. The search results from each database were imported into an Endnote X9 reference manager (Thomson Reuters, Toronto, ON, Canada).

Eligibility criteria

The inclusion criteria were publication in English andepidemiological studies that reported the prevalence of PA counseling in a primary care setting. The exclusion criteria were duplicates, unpublished studies, conference abstracts, expert opinion excerpts, review articles (i.e., systematic, scoping, and narrative reviews), protocols, and trial registrations (Supplementary file 1, Table S2).

Study selection

The lead author (AW) screened the titles and abstracts. Uncertainties were resolved by discussion with another author (SC). Two authors (AW and SL) then read the full-text articles and identified each as “Yes”, “No”, or “Maybe”. The level of agreement was determined based on the percent agreement and Cohen’s kappa (ĸ) using an online statistic calculator (GraphPad by Dotamics: https://www.graphpad.com/quickcalcs/kappa1/), with ĸ values of 0–0.20, 0.21–0.39, 0.40–0.59, 0.60–0.79, 0.80–0.90, and > 0.90 indicating no agreement, minimal agreement, weak agreement, moderate agreement, strong agreement, and almost perfect agreement, respectively.20 Any discrepancies between the two authors (“Yes”/“Maybe”, “No”/“Maybe”, “Maybe”/“Maybe”, or “Yes”/“No”) were resolved by discussion with another author (CL).

Data extraction

The lead author (AW) extracted data using a data extraction form developed by the review team in Microsoft Word (Microsoft Inc., Redmond, WA, USA). The following information was extracted from each article: article title, name of first author, year of publication, country of study, study design, study participants and setting, characteristics and contents of PA counseling, and prevalence of PA counseling with 95% confidence interval (CI), if available. Another author (SL) cross-checked the data extraction forms, and any disagreements were resolved by consensus.

Quality assessment of individual studies

The quality of each study was assessed by two authors (AW and SL) using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) critical appraisal checklist for studies reporting prevalence data. The appraisal tool consists of nine questions with four standard answers (“Yes”, “No”, “Unclear”, or “Not applicable”). Based on the judgment of reviewers, the result for each study is “Include”, “Exclude”, or “Seek further information”.21,22

Data synthesis

The data from the data extraction forms, encompassing both qualitative data (e.g., characteristics and content of PA counseling) and quantitative data (e.g., prevalence of PA counseling), were synthesized and presented in a narrative summary. For studies reporting multiple values of prevalence, the most recent prevalence was used in the narrative summary.

Meta-analysis was conducted in R version 4.2.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) using the meta package.23 The pooled prevalence was calculated based on the number of participants who received PA counseling divided by the entire number of eligible participants. The reviewers contacted the corresponding author of each study via email to clarify unclear or missing numbers. If the corresponding authors did not respond within 2 weeks, the reviewers calculated the missing numbers based on the available data or, if this was not possible, excluded the study from the meta-analysis. Statistical heterogeneity was explored using the Cochran’s Q test (chi-square statistics) and quantified by I2. Owing the heterogeneity among the studies, a random-effects model was used to calculate the pooled prevalence, the prevalence of each medical condition and its 95% CIs. For studies reporting multiple values of prevalence, the most recent prevalence was included in the meta-analysis. A funnel plot was created to evaluate potential publication bias.

Results

Study selection

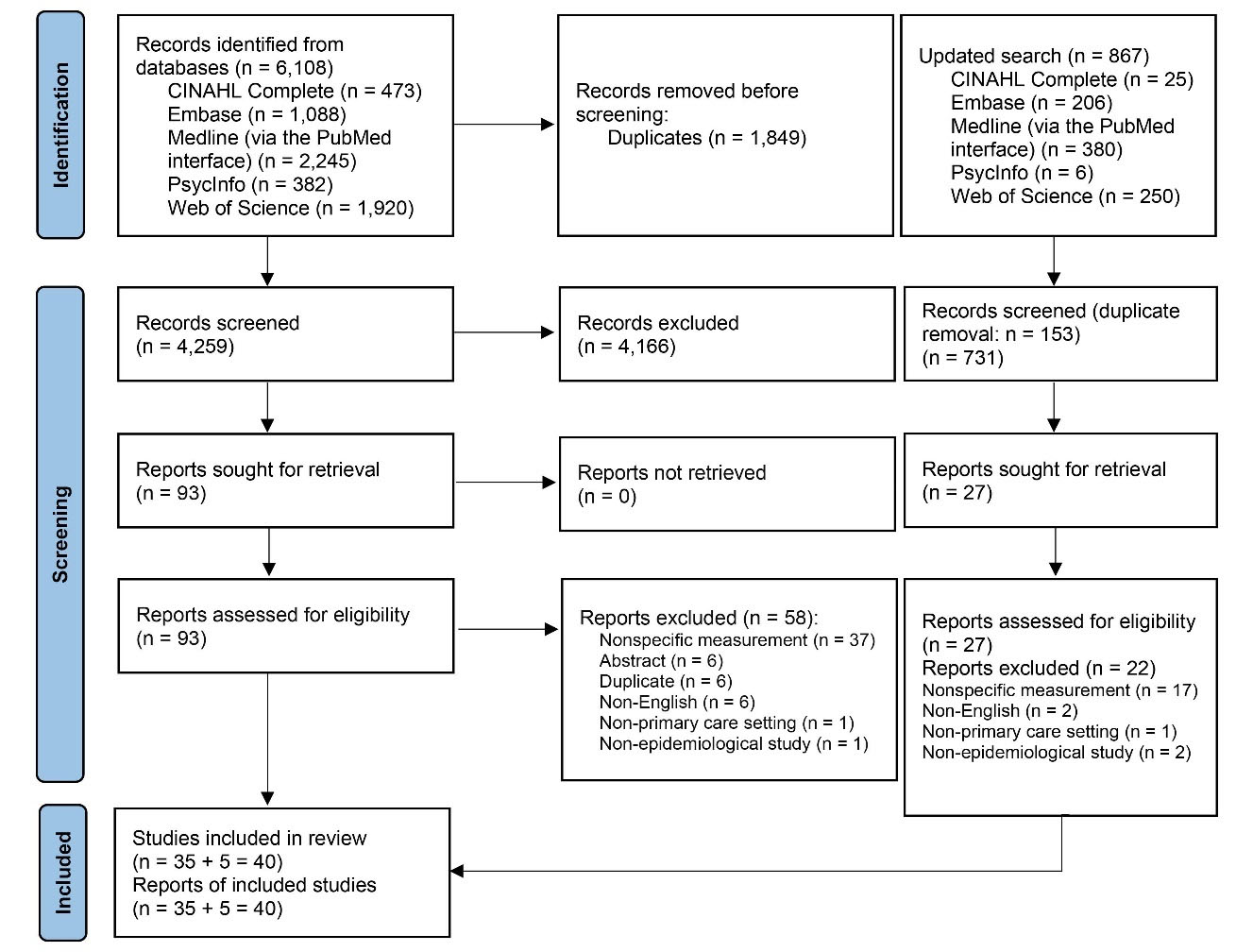

A total of 6975 articles were retrieved from the five databases, and 2002 duplicates were excluded. After screening the titles and abstracts, a further 4897 articles were excluded. The full-texts of the remaining 120 articles were then independently reviewed by two reviewers; their percentage agreement was 96.67% (116 out of 120 articles) and ĸ was 0.927 (standard error: 0.035, 95% CI: 0.859 to 0.995). Finally, 40 articles (representing 40 studies) were included in the analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram

.

PRISMA flow diagram

Study characteristics and quality assessment of studies

The 40 included studies were published between 1992 and 2022. They were conducted in 17 countries: USA (n = 11), Australia (n = 5), Brazil (n = 3), Germany (n = 3), Barbados (n = 2), Lithuania (n = 2), New Zealand (n = 2), Poland (n = 2), UK (n = 2), Belgium (n = 1), Canada (n = 1), China (n = 1), Jamaica (n = 1), Spain (n = 1), Sweden (n = 1), Switzerland (n = 1), and Tanzania (n = 1). Four studies addressed PA counseling by direct observation or reviewing videotapes of doctor–patient visits.24-27 The number of eligible participants ranged from 14 to 90 240 (Table 1). The quality assessment scores (JBI scores) of the included studies ranged from 5 to 9 out of 9: 5/9 (n = 6), 6/9 (n = 12), 7/9 (n = 10), 8/9 (n = 7), and 9/9 (n = 5) (Table 1 and Supplementary file 1, Table S3).

Table 1.

Study characteristics

|

First author and year of publication (country)

|

JBI checklist

|

Data collection

|

Participants

|

Characteristics of PA counseling

|

Prevalence

|

Adams et al 201028

(Barbados) |

6/9 |

Chart audit |

343 charts of patients aged ≥ 40 with HT from public and private clinics |

Recording exercise advice in patient’s chart |

153/343 = 44.6% |

Adams et al 201129

(Barbados) |

6/9 |

Chart audit |

253 charts of patients aged ≥ 40 with DM from public and private clinics |

Recording exercise advice in patient’s chart |

124/253 = 49.0% |

Ahmed et al 201730

(USA) |

6/9 |

Household interview surveys in 2000, 2005, and 2010 |

Adults aged ≥ 18 who were able to perform PA (without physical disability) and visited a doctor or other health care provider in the past 12 months

(n = 23,656 in 2000; n = 26 152 in 2005; n = 21 905 in 2010) |

“During the past 12 months, did a doctor or other health professional recommend that you begin or continue to do any type of exercise or physical activity?” |

2000 (n = 23 656): 22.9% (95% CI 22.0 to 23.8)

2005 (n = 26 152): 30.4% (95% CI 29.7 to 31.0)

2010 (n = 21 905): 33.6% (95% CI: 32.8 to 34.4) |

Barbosa et al 201731

(Brazil) |

8/9 |

Face-to-face interview |

785 patients aged ≥ 20 with HT

823 patients aged ≥ 20 with DM with or without HT |

“Has any health provider of the Family Health Strategy ever counseled you to modify (improve) your physical activity habits? (Yes/No)” |

HT: 406/785 = 51.7%

DM: 475/823 = 57.7% |

Bovier et al 200732

(Switzerland) |

7/9 |

Face-to-face assessment and interview of the participating physician to analyze the last 20 medical records of patients who visited the physician’s office |

186 community-based primary care physicians with 3684 patient records

Records of patients with DM (n = 350, however 345 were eligible for PA counseling) and pre-DM (n = 181) who had a follow-up in the last 12 months were analyzed |

Assessing the adherence to recommended standards of diabetes care, including promotion of daily PA |

DM: 273/345 = 79.1%

Pre-DM: 108/181 = 59.7% |

Croteau et al 200633

(New Zealand) |

8/9 |

National postal survey |

8291 adults (61% response rate) |

Asking whether a doctor or practice nurse advised PA or gave a Green Prescription (written and verbal PA prescription scheme) in the past 12 months |

PA advice: 1046/8291 = 12.6%

Green Prescription: 235/8,291 = 2.8% |

Daly et al 201534

(New Zealand) |

9/9 |

Telephone interview |

265 patients with DM (out of 308 sampled patients = 96% of the sampled patients) seen by participating primary health care nurses |

“Did you give advice about diet or physical activity?”

Details of PA counseling were asked about, such as advice on increasing PA level, walking, mobility-limited activities, swimming, joining a gym or exercise class |

PA advice: 175/265 = 66.0%

Green Prescription: 11/265 = 4.2% |

Davis-Ajami et al 202135

(USA) |

7/9 |

Questionnaire |

1039 pre-DM adults aged ≥ 20 with overweight/obesity (BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2)

Among 1039 participants, 798 participants received lifestyle advice (241 participants did not receive lifestyle advice) |

Being advised to increase PA or exercise |

Exercise advice (total participants: n = 1,039): 67.6%

Exercise advice (only participants receiving lifestyle advice: n = 798): 87.9% |

Desai et al 200236

(USA) |

8/9 |

Chart review |

90 240 people with obesity (BMI ≥ 27 kg/m2) and/or HT and with/without mental conditions |

Evidence of receipt of exercise counseling in the past 2 years

Exercise counseling included needs for regular PA, benefits of PA, and methods for increasing PA |

Overall: 88.5%

No mental disorder: 88.7%

Psychiatric disorder: 88.5%

Substance use: 86.3%

Psychiatric disorder and substance use: 85.7% |

Eakin et al 200737

(Australia) |

6/9 |

Self-reported survey |

Of 2,478 participants, 1999 participants (80.67%) visited a GP at least once in the last 12 months |

“Did you receive any advice from your doctor about exercise or physical activity?” |

483/1999 = 24.2% |

Edward et al 202024

(Tanzania) |

7/9 |

Direct observation of patient consultation |

Of 69 new patients aged ≥ 30, 14 were diagnosed with HT |

Advising patients with HT to increase PA |

3/14 = 21.43% |

Egede et al 200238

(USA) |

7/9 |

Self-reported survey |

Adults aged ≥ 18: 9,496 adults with DM and 150 493 adults without DM

PA counseling was assessed among adults with a BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 who had a checkup in the past 12 months |

Receiving counseling about regular PA during at least one checkup in the past 12 months |

DM (n = 875): 67.4% (95% CI 63.2 to 71.7)

No DM (n = 10154): 36.0% (95% CI: 34.6 to 37.4) |

Eldemire-Shearer et al 200939

(Jamaica) |

6/9 |

Face-to-face interview |

738 adults aged ≥ 50 who visited health centers/hospitals/primary care services |

Being advised about PA |

24.5% |

Flocke et al 200425

(USA) |

7/9 |

Direct observation of patient visits by research nurses

Recall of health behavior advice was assessed by using an exit questionnaire |

2,670 adults aged ≥ 18 who visited their family physicians and completed a patient exit survey |

Exercise advice by family physicians |

Direct observation: 603/2670 = 22.6%

Patient recall 260/603 = 43.1% |

Foss et al 199640

(UK) |

5/9 |

Self-administered questionnaire |

2,676 adults aged ≥ 18 with mild to moderate HT (71% of participants recalled receiving lifestyle advice, so the number of participants who received lifestyle advice was 1900) |

Advice on exercise |

722/1900 = 38.0% |

Gabrys et al 201517

(Germany) |

7/9 |

Retrieved data from two cross-sectional health interview and examination surveys (1997–1999 and 2008–2011) |

Adults aged 18–64: M = 2891 and F = 3078 in the 1997–1999 survey; M = 2,789 and F = 3149 in the 2008–2011 survey |

Self-reported PA counseling provided by a physician in the last 12 months |

1997–1999:

F = 9.3%; M = 11.1%; with DM = 10.8%; without DM = 11.1%; with HT = 14.1%; without HT = 10.6%; with CHD = 17.7%; without CHD = 10.8%; with cancer = 9.0%; without cancer = 11.1%

2008–2011:

F = 7.7%; M = 9.4%; with DM = 29.8%; without DM = 8.6%; with HT = 16.8%; without HT = 8.1%; with CHD = 24.0%; without CHD = 10.9%; with cancer = 14.0%; without cancer = 9.3% |

Geerling et al 201941

(Australia) |

5/9 |

Online questionnaire and hard-copy questionnaire completed by participants |

381 adults aged ≥ 18 with type 2 DM |

Using counseling techniques (each one of the 14 behavior change techniques) for PA |

279/381 = 73.2% (receiving general advice – PA is important) |

Gowin et al 200926

(Poland) |

6/9 |

Direct observation of consultation and medical record review for preventive procedures in the past year |

450 adults aged ≥ 40 (F = 267 and M = 183) who visited 113 GPs (four consecutive patients were observed per GP) |

11 preventive procedures, including PA counseling |

37/450 = 8.2%

F: 23/267 = 8.6%

M: 14/183 = 7.6% |

Hinrichs et al 201142

(Germany) |

6/9 |

Telephone interview |

1937 older adults aged ≥ 65 who used to participate in a cohort study (7 years before this study) (310 participants were excluded due to incomplete data or advice to rest (did not recommend exercise)); 1,627 participants (F = 854 and M = 773) were included in the analysis |

Advice to get regular exercise in the past 12 months |

534/1627 = 32.8%

F = 30.0%

M = 36.0% |

Hu et al 202143

(China) |

8/9 |

In-person questionnaire |

454 patients with chronic conditions |

“Did the physician provide PA advice to you just now?” If the participants were advised about PA, they were asked about whether they received advice on frequency, intensity, duration, and type. |

87/454 = 19.2%

(8/87 = 9.2% received all four components) |

| Johansson et al 200544 (Sweden) |

6/9 |

Postal questionnaire |

6734 patients aged 18–79 who visited GPs at primary care centers (4163 participants responded to the question about exercise advice) |

Advice on lifestyle habits, including physical exercise |

677/4163 = 16.3% |

Juré et al 202245

(Belgium) |

8/9 |

Chart review |

3055 patients (F = 2310 and M = 745) aged ≥ 18 with chronic venous disease from 253 GPs (out of 3,103 sampled patients = 98.4% of the sampled patients) |

Advice on PA |

1,328/3055 = 43.5%

F: 994/2310 = 43.0%

M: 334/745 = 44.8% |

| Klumbiene et al 200646 (Lithuania) |

6/9 |

Mailed questionnaire from three surveys in 2000, 2002, and 2004 |

2049 adults (F = 1156 and M = 893) aged 20–64 with overweight and obesity who visited GPs in the past 12 months based on three surveys |

“During the last year (12 months) have you been advised to increase your physical activity?” |

F = 19.2%

M = 15.9% |

| Kriaucioniene et al 201947 (Lithuania) |

6/9 |

Mailed questionnaire from eight surveys in 2000, 2002, 2004, 2006, 2008, 2010, 2012, and 2014 |

5867 adults aged 20–64 with overweight and obesity who visited GPs in the past 12 months based on eight surveys (2000: n = 699; 2002: n = 680; 2004: n = 670; 2006: n = 705; 2008: n = 738; 2010: n = 883; 2012: n = 779; and 2014: n = 713) |

“During the last year (12 months) have you been advised by a GP to increase your physical activity?” |

2000: 11.9% (95% CI: 9.6 to 14.1)

2002: 13.8% (95% CI: 11.3 to 16.3)

2004: 11.7% (95% CI: 9.4 to 14.1)

2006: 12.7% (95% CI: 10.3 to 15.1)

2008: 18.0% (95% CI: 15.3 to 20.8)

2010: 17.2% (95% CI: 14.9 to 19.6)

2012: 15.3% (95% CI: 12.8 to 17.8)

2014: 11.6% (95% CI: 9.2 to 13.9)

Overall (2000–2014): 14.2% (95% CI: 13.3 to 15.1) |

| Lau et al 201348 (USA) |

5/9 |

Self-reported surveys in 2005 and 2007 |

Young adults aged 18–26 who responded to California Health Interview Survey in 2005 (n = 3670) and 2007 (n = 3,621); 2955 participants in 2005 responded to a question regarding exercise counseling (there was no question regarding exercise counseling in the 2007 survey) |

“Did a health provider give you information about how much or what kind of exercise you get?” |

Overall = 22.0%

F = 24.5%

M = 19.1% |

| Martínez-Gómez et al 201349 (Spain) |

8/9 |

Computer-assisted telephone interview with a structured questionnaire and two home visits for physical examination, biological sample (blood and urine) collection, and dietary history |

12 985 adults aged ≥ 18 (1034 were excluded or missing); 11 951 participants were included |

“Have you ever been counseled by your physician or nurse to do PA, in particular, walking for at least 30 min several days a week?” |

5,591/11,951 = 46.2% (95% CI: 45.0 to 47.4%)

F (n = 6,851): 50.2% (95% CI: 48.6 to 51.8)

M (n = 6,191): 42.1% (40.4 to 43.8) |

| Nguyen et al 201150 (USA) |

6/9 |

Face-to-face interview from 2002–2006 (5 surveys) |

1787 Mexican-American adults (F = 1,126 and M = 661) aged ≥ 18 with obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) and a usual health care provider |

“Has a doctor or other health care professional ever advised you to exercise more?” |

Overall: 988/1,787 = 55.9%

F: 655/1126 = 58.2%

M: 333/661 = 50.4% |

| Ory et al 200627 (USA) |

5/9 |

Videotape (doctor–patient encounter) review |

423 older adults aged ≥ 65 who were seen by 36 doctors at three primary care sites |

Doctor–patient discussion on PA or nutrition or both PA and nutrition |

PA only: 39.2%

Both PA and nutrition: 22.0%

Total PA discussion: 61.2% |

| Robertson et al 201151 (Australia) |

5/9 |

Computer-assisted telephone interview |

1261 adults aged ≥ 18 (one eligible person per household) |

Recommendations on doing some exercise/PA or increasing exercise/PA by a health professional in the past 12 months; the follow-up questions included questions on type of health professional and type of PA |

PA recommendations by any health professional: 311/1,261 = 24.7%

PA recommendations by GP: 225/1,261 = 17.8%

Walking was the most common type of PA recommended by GPs: 175/225 = 77.8% |

| Dos Santos et al 202152 (Brazil) |

9/9 |

Face-to-face interview |

779 adults (F = 544 and M = 235) aged ≥ 18 living in urban areas who visited basic health units (excluded a person who used the basic health unit for the first time) |

“During the last year (12 months), any time you were at the basic health unit, did you receive PA counseling during the consultation by a health professional (advice, tips, or guidance on PA to change/improve your health)?” |

Overall: 335/779 = 43.0% (95% CI: 39.5 to 46.4%)

F: 43.6%

M: 41.7% |

| Short et al 201653 (Australia) |

7/9 |

Online questionnaire |

1799 adults aged ≥ 18 |

PA recommendations by a GP in the past 12 months, including type (i.e., aerobic PA, resistance-based PA, flexibility, balance, non-specific PA, cannot remember) and amount (duration and frequency) |

328/1799 = 18.2%

Received specific advice: 253/328 = 77.1%

Most common types:

aerobic PA: 150/253 = 59.3%; resistant PA: 34/253 = 13.4%; flexibility: 29/253 = 11.5%; balance: 11/253 = 4.4%

Received specific amount of PA: 136/253 = 53.8% |

| Shuval et al 201454 (USA) |

5/9 |

Questionnaire |

157 adults aged 40–79 |

General PA counseling in the past 12 months; components (5As: ask, advise, agree, assist, and arrange) |

General PA counseling: 84/157 = 53.5%

Ask: 5/157 = 3.2%

Advise - verbal: 71/157 = 45.2%; written: 22/157 = 14.0%

Agree: 54/157 = 34.4%

Assist – overcoming barriers: 22/157 = 14.0%; identifying community resources and social support: 16/157 = 10.2%

Arrange: 18/157 = 11.5% |

| Silagy et al 199255 (UK) |

8/9 |

Mailed questionnaire |

4941 adults aged 35–64 who visited GPs in the past 12 months and subsequently attended for a health check |

"In the last 12 months has a doctor or nurse advised you to take more exercise/stop smoking/drink less alcohol/change your diet or lose weight?" |

PA advice: 222/4941 = 4.5% |

| Sinclair et al 200856 (Canada) |

7/9 |

Questionnaire |

1562 adults aged ≥ 18 who reported having a regular family physician |

“In visits to your usual family doctor [health care provider], how often were the following subjects discussed with you: advice on healthy eating and advice on appropriate exercise for you.”

The analysis was performed according to two categories (often/always and never/rarely) |

Overall prevalence of “often/always” discussed exercise = 42.0% |

| Smith et al 201957 (Australia) |

7/9 |

Case note review (10–20 consecutive patients visited 365 GPs) |

6512 patients (F = 3,512 and M = 3,000) with HT who visited GPs |

PA prescription |

Overall: 2518/6512 = 38.7%

F: 1325/3512 = 37.7%

M: 1193/3000 = 39.8% |

de Souza et al 202258

(Brazil) |

9/9 |

Face-to-face interview |

779 adults (F = 544 and M = 235) aged ≥ 18 who visited primary care units |

“During the past year (12 months), in a visit to the healthcare unit, did you receive physical activity counseling while in consultation with a healthcare professional (advice, tips or orientation on physical activity or exercise)?” |

335/779 = 43.0% |

Tiffe et al 202159

(Germany) |

6/9 |

Face-to-face interview |

665 participants aged 30-79 without cardiovascular disease |

Advice by a physician to increase PA |

52.1% |

| Wee et al 199960 (USA) |

9/9 |

In-person survey |

9711 adults aged ≥ 18 who had a medical check-up in the previous year; 9299 participants responded to a question regarding having exercise counseling provided by a physician |

“During your last (medical) check-up, did the doctor recommend that you begin or continue to do any type of exercise or PA?" |

Overall = 34.0%

F = 33.0%

M = 34.0% |

Znyk et al 202261

(Poland) |

9/9 |

Face-to-face interview |

896 adults aged ≥ 18 who visited primary care |

“Has the family doctor ever talked to you about physical activity and exercise?” |

Overall: 355/896 = 39.6%

Overweight/obesity: 198/402 = 49.2% |

| Zwald et al 201962 (USA) |

7/9 |

Interview |

11 062 adults aged ≥ 20; 8410 participants were eligible (utilizing health care services in the past year) for the analysis |

“To lower your risk for certain diseases, during the last 12 months have you ever been told by a doctor or health professional to increase your PA or exercise?” |

Overall (n = 8410): 42.9% (95% CI: 40.8 to 44.9)

DM (n = 1570): 69.8% (95% CI: 66.5 to 72.8)

HT (n = 3447): 56.5% (95% CI: 53.8 to 59.2)

Obesity (n = 3390): 63.0% (95% CI: 60.3 to 65.7) |

CI, confidence interval; BMI, body mass index; CHD, coronary heart disease; DM, diabetes mellitus; F, female; GP, general practitioner; HT, hypertension; JBI, Joanna Briggs Institute; M, male; PA, physical activity.

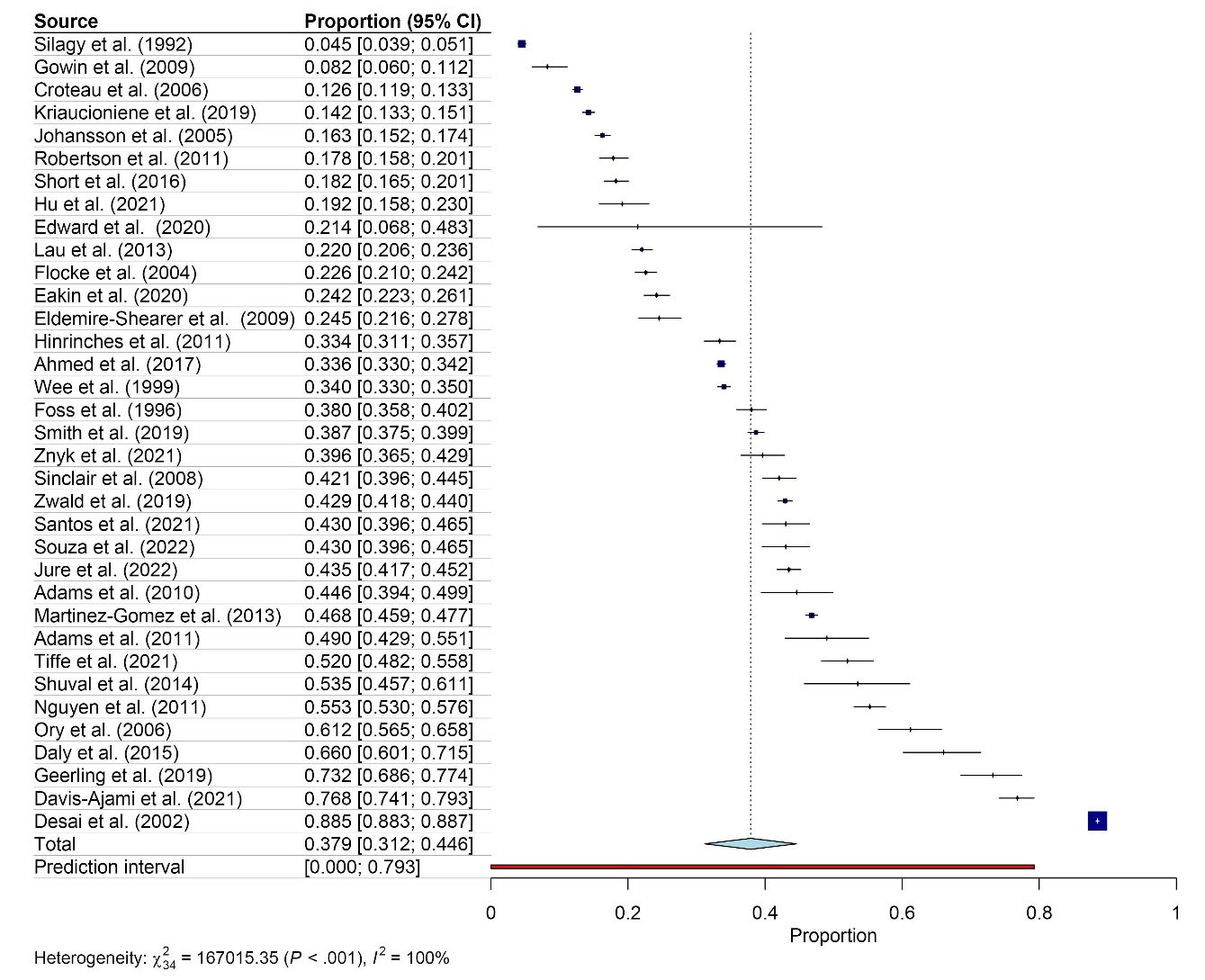

Prevalence of physical activity counseling

The meta-analysis of 35 studies with a total of 199 830 participants showed that the pooled prevalence of PA counseling in primary care was 37.9% (95% CI: 31.2 to 44.6) (Figure 2 and Supplementary file 1, Table S4). Five studies were not included in the meta-analysis because it did not report the overall prevalence of PA counseling of the entire study participants. For example, they reported the prevalence in females and males separately.

Figure 2.

Pooled proportion of physical activity counseling

.

Pooled proportion of physical activity counseling

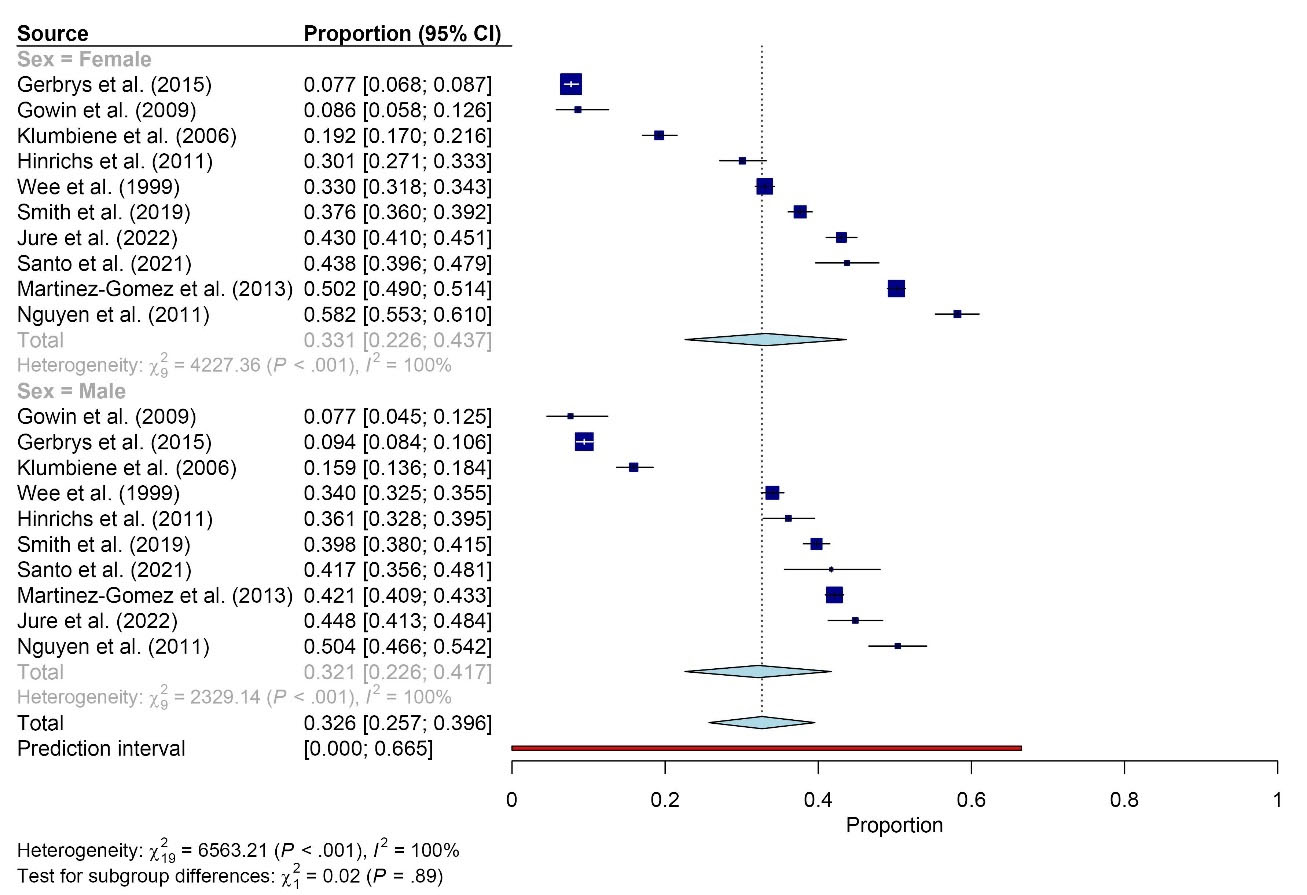

The pooled prevalence of PA counseling in primary care by sex was 33.1% (95% CI: 22.6 to 43.7) for females (n = 10; 25,255 participants) and 32.1% (95% CI: 22.6 to 41.7) for males (n = 10; 19,283 participants) (Figure 3 and Supplementary file 5, Table S5).

Figure 3.

Pooled proportion of physical activity counseling by sex

.

Pooled proportion of physical activity counseling by sex

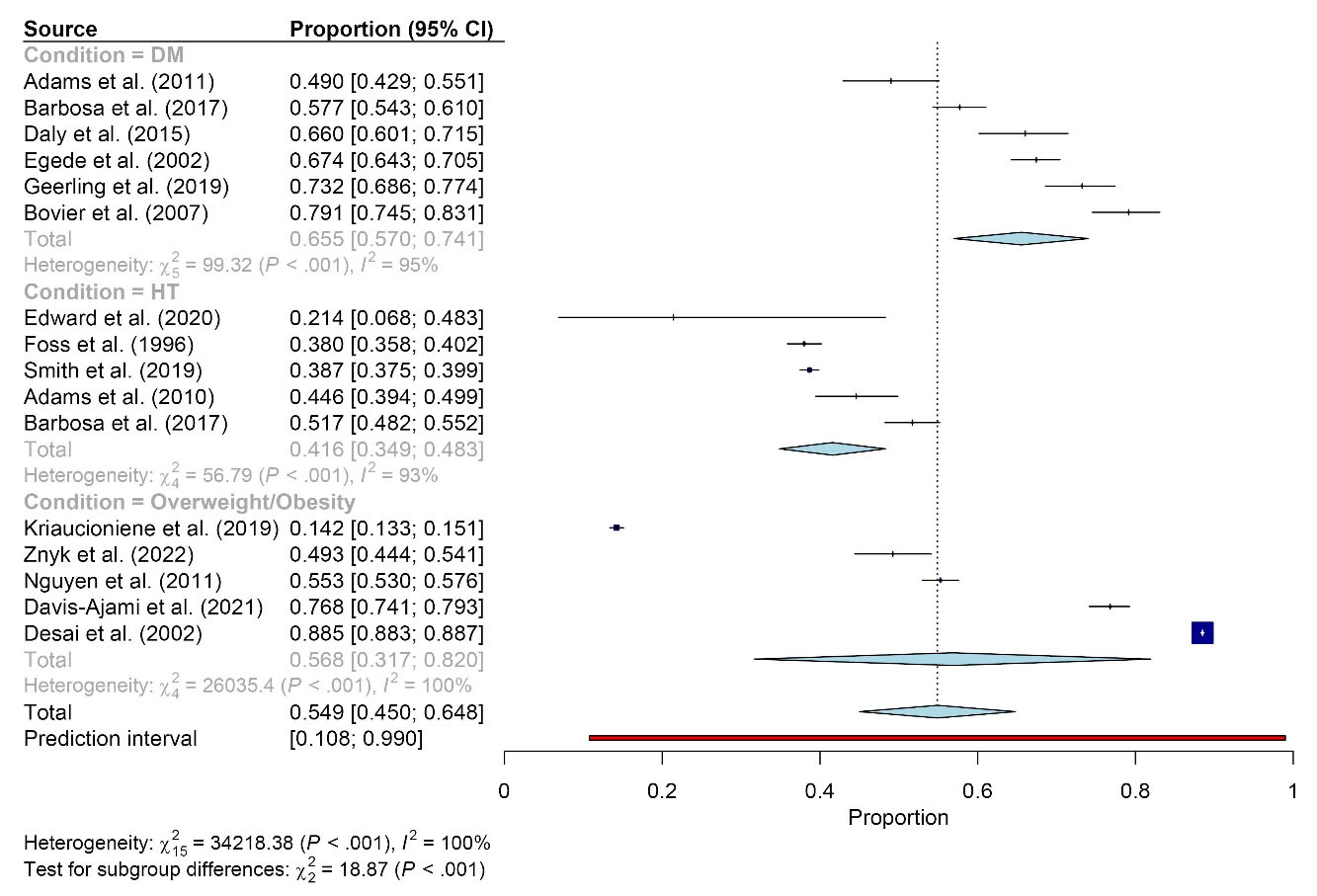

The pooled prevalence of PA counseling in primary care was 65.5% (95% CI: 57.0 to 74.1; n = 6; 2942 participants) among people with diabetes mellitus (DM), 41.6% (95% CI: 34.9 to 48.3; n = 5; 9554 participants) among people with hypertension (HT), and 56.8% (95% CI: 31.7 to 82.0; n = 5; 99 335 participants) among people with overweight or obesity (Figure 4 and Supplementary file 6, Table S6).

Figure 4.

Pooled proportion of physical activity counseling by medical condition. Abbreviations: DM, diabetes mellitus; HT, hypertension

.

Pooled proportion of physical activity counseling by medical condition. Abbreviations: DM, diabetes mellitus; HT, hypertension

Heterogeneity of studies and potential publication bias

There were high levels of heterogeneity among studies. The I2 of the overall meta-analysis of 35 studies was 100% (P < 0.001) (Figure 2). The meta-analyses by sex and medical condition showed high levels of heterogeneity for both sexes (I2 = 100%, P < 0.001) (Figure 3) and medical conditions (DM: I2 = 95%, P < 0.001; HT: I2 = 93%, P < 0.05; and overweight or obesity: I2 = 100%, P < 0.001) (Figure 4). Figure 5 shows an asymmetrical funnel plot.

Discussion

This systematic review included 40 studies conducted in 17 countries from four out of six regions according to the WHO categories (Region of the Americas = 18 studies, European Region = 13 studies, Western Pacific Region = 8 studies, and African Region = 1 study).63 The overall prevalence of PA counseling calculated from 35 studies (199 830 participants) was 37.9%. By sex, the prevalence was 33.1% for females (10 studies; 25 255 participants) and 32.1% for males (10 studies; 19,283 participants). By medical condition, the prevalence among people with DM, HT, and overweight/obesity was 65.5% (6 studies; 2942 participants), 41.6% (5 studies; 9554 participants), and 56.8% (5 studies; 99 335 participants), respectively.

Regarding the quality of individual studies based on the JBI critical appraisal checklist for studies reporting prevalence data, there were some issues. Most of the studies had unclear information about the appropriateness of sampling methods (20/40 studies, 50.0%), the adequacy of sample sizes (32/40 studies, 80.0%), and the adequacy of response rates (29/40 studies, 72.5%). This suggests the possibility of selection bias and non-response bias in many studies.64 Therefore, the results of this systematic review should be interpreted with caution based on these biases.

The prevalence of PA counseling varied across various settings from low (4.5%) to high (88.5%). The previous systematic review by Hall et al reported the prevalence of PA screening in primary care ranging from 2.4% to 100% and the prevalence of PA advice in primary care ranging from 0.6% to 100%.65 However, the aforementioned systematic review included different types of studies (e.g., cross-sectional studies, qualitative studies) and sources of information on PA counseling (e.g., reported by health professionals and patients).65 In the present systematic review, primary studies that reported the prevalence of PA counseling based on estimates from health care providers were excluded from the pooled results in order to avoid overestimation. The previous systematic review did not perform meta-analysis.65 The present systematic review reported the pooled prevalence based on meta-analysis of primary studies.

The meta-analyses revealed greater prevalence of PA counseling in females compared to males. This observation highlights the disparity in practices between these two population groups. One potential explanation is that primary care providers prioritize females as a higher-risk demographic for insufficient PA. The global data also supports that females were more likely to be physically inactive compared to males.66-68 Regarding medical conditions, the meta-analyses demonstrated higher prevalence of PA counseling among individuals with DM, HT, and overweight/obesity compared to the overall prevalence. PA is regarded as an essential treatment and preventive strategy for these medical conditions.69-71 Consequently, the emphasis on PA counseling in primary care was particularly pronounced within these populations.

High levels of heterogeneity were identified in all meta-analyses. One potential reason for this is that there were different data collection and outcome measurement methods among the individual studies, which may impact the reported prevalence of PA counseling in different studies. Another potential reason was that there is a lack of standard guidelines for PA counseling in primary care. The 2020 WHO guidelines on PA state the recommendations for clinical populations; however, this report did not indicate specific guidelines for clinical practices.4 Although various approaches to PA counseling in primary care have been published,11,72-76 the development of standard guidelines for PA counseling in primary care is recommended.

Most of the included studies in this review (39/40, 97.5%) were conducted in three regions (Region of the Americas, European Region, and Western Pacific Region).63 This trend was similar to the findings on research productivity in the field of PA research that showed a large proportion of publications have been produced in these three regions.77,78 Our finding may reflect the influence of research productivity and the contribution of studies on PA counseling in primary care in the various regions. In the other regions of the world, there is a need to highlight PA research, which may improve insights into PA counseling in primary care.

This systematic review has several strengths. First, it focused on a specific setting, primary care. Second, it involved meta-analyses of the primary care population and subgroup populations (by sex and medical condition). Third, studies that reported the prevalence of PA counseling estimated by health care providers were excluded from the pooled results to avoid overestimation. A major limitation of the review is that the differences in PA counseling and outcome measurement methods among primary studies may affect the pooled prevalence and cause high levels of heterogeneity in the meta-analyses.

Conclusion

The prevalence of PA counseling in primary care is low (37.9%) and varies between studies (from 4.5% to 88.5%). PA counseling is more common among people with DM, overweight/obesity, and HT. Due to the high levels of study heterogeneity and different PA counseling approaches, there is a need to develop practical guidelines for PA counseling in primary care.

Competing Interests

The authors declared no competing interest.

Ethical Approval

Not applicable.

Supplementary Files

Supplementary file 1 contains Table S1-S6.

(pdf)

References

- Elley CR, Kerse N, Arroll B, Robinson E. Effectiveness of counselling patients on physical activity in general practice: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2003; 326(7393):793. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7393.793 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Gagliardi AR, Abdallah F, Faulkner G, Ciliska D, Hicks A. Factors contributing to the effectiveness of physical activity counselling in primary care: a realist systematic review. Patient Educ Couns 2015; 98(4):412-9. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2014.11.020 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Kerse N, Elley CR, Robinson E, Arroll B. Is physical activity counseling effective for older people? A cluster randomized, controlled trial in primary care. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005; 53(11):1951-6. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00466.x [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Bull FC, Al-Ansari SS, Biddle S, Borodulin K, Buman MP, Cardon G. World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Br J Sports Med 2020; 54(24):1451-62. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2020-102955 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Kyu HH, Bachman VF, Alexander LT, Mumford JE, Afshin A, Estep K. Physical activity and risk of breast cancer, colon cancer, diabetes, ischemic heart disease, and ischemic stroke events: systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. BMJ 2016; 354:i3857. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i3857 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Reiner M, Niermann C, Jekauc D, Woll A. Long-term health benefits of physical activity--a systematic review of longitudinal studies. BMC Public Health 2013; 13:813. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-813 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Samitz G, Egger M, Zwahlen M. Domains of physical activity and all-cause mortality: systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of cohort studies. Int J Epidemiol 2011; 40(5):1382-400. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyr112 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ekelund U, Tarp J, Steene-Johannessen J, Hansen BH, Jefferis B, Fagerland MW. Dose-response associations between accelerometry measured physical activity and sedentary time and all cause mortality: systematic review and harmonised meta-analysis. BMJ 2019; 366:l4570. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l4570 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Füzéki E, Weber T, Groneberg DA, Banzer W. Physical activity counseling in primary care in Germany-an integrative review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020; 17(15):5625. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17155625 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Lion A, Vuillemin A, Thornton JS, Theisen D, Stranges S, Ward M. Physical activity promotion in primary care: a Utopian

quest?. Health Promot Int 2019; 34(4):877-86. doi: 10.1093/heapro/day038 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Wattanapisit A, Wattanapisit S, Wongsiri S. Overview of physical activity counseling in primary care. Korean J Fam Med 2021; 42(4):260-8. doi: 10.4082/kjfm.19.0113 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Dumith SC, Gigante DP, Domingues MR. Stages of change for physical activity in adults from Southern Brazil: a population-based survey. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2007; 4:25. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-4-25 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Thanamee S, Pinyopornpanish K, Wattanapisit A, Suerungruang S, Thaikla K, Jiraporncharoen W. A population-based survey on physical inactivity and leisure time physical activity among adults in Chiang Mai, Thailand, 2014. Arch Public Health 2017; 75:41. doi: 10.1186/s13690-017-0210-z [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Young MD, Plotnikoff RC, Collins CE, Callister R, Morgan PJ. Social cognitive theory and physical activity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev 2014; 15(12):983-95. doi: 10.1111/obr.12225 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Orrow G, Kinmonth AL, Sanderson S, Sutton S. Effectiveness of physical activity promotion based in primary care: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2012; 344:e1389. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e1389 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Florindo AA, Mielke GI, de Oliveira Gomes GA, Ramos LR, Bracco MM, Parra DC. Physical activity counseling in primary health care in Brazil: a national study on prevalence and associated factors. BMC Public Health 2013; 13:794. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-794 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Gabrys L, Jordan S, Schlaud M. Prevalence and temporal trends of physical activity counselling in primary health care in Germany from 1997-1999 to 2008-2011. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2015; 12:136. doi: 10.1186/s12966-015-0299-9 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021; 372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD. Updating guidance for reporting systematic reviews: development of the PRISMA 2020 statement. J Clin Epidemiol 2021; 134:103-12. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2021.02.003 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- McHugh ML. Interrater reliability: the kappa statistic. Biochem Med (Zagreb) 2012; 22(3):276-82. [ Google Scholar]

- Munn Z, Moola S, Lisy K, Riitano D, Tufanaru C. Methodological guidance for systematic reviews of observational epidemiological studies reporting prevalence and cumulative incidence data. Int J Evid Based Healthc 2015; 13(3):147-53. doi: 10.1097/xeb.0000000000000054 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Migliavaca CB, Stein C, Colpani V, Munn Z, Falavigna M. Quality assessment of prevalence studies: a systematic review. J Clin Epidemiol 2020; 127:59-68. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2020.06.039 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Balduzzi S, Rücker G, Schwarzer G. How to perform a meta-analysis with R: a practical tutorial. Evid Based Ment Health 2019; 22(4):153-60. doi: 10.1136/ebmental-2019-300117 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Edward A, Hoffmann L, Manase F, Matsushita K, Pariyo GW, Brady TM. An exploratory study on the quality of patient screening and counseling for hypertension management in Tanzania. PLoS One 2020; 15(1):e0227439. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0227439 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Flocke SA, Stange KC. Direct observation and patient recall of health behavior advice. Prev Med 2004; 38(3):343-9. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.11.004 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Gowin E, Avonts D, Horst-Sikorska W, Ignaszak-Szczepaniak M, Michalak M. Gender makes the difference: the influence of patients’ gender on the delivery of preventive services in primary care in Poland. Qual Prim Care 2009; 17(5):343-50. [ Google Scholar]

- Ory MG, Yuma PJ, Hurwicz ML, Jarvis C, Barron KL, Tai-Seale T. Prevalence and correlates of doctor-geriatric patient lifestyle discussions: analysis of ADEPT videotapes. Prev Med 2006; 43(6):494-7. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2006.06.015 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Adams OP, Carter AO. Are primary care practitioners in Barbados following hypertension guidelines? - a chart audit. BMC Res Notes 2010; 3:316. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-3-316 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Adams OP, Carter AO. Are primary care practitioners in Barbados following diabetes guidelines? - a chart audit with comparison between public and private care sectors. BMC Res Notes 2011; 4:199. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-4-199 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ahmed NU, Delgado M, Saxena A. Trends and disparities in the prevalence of physicians’ counseling on exercise among the U.S. adult population, 2000-2010. Prev Med 2017; 99:1-6. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.01.015 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Barbosa JMV, de Souza WV, Ferreira RWM, de Carvalho EMF, Cesse EAP, Fontbonne A. Correlates of physical activity counseling by health providers to patients with diabetes and hypertension attended by the Family Health Strategy in the state of Pernambuco, Brazil. Prim Care Diabetes 2017; 11(4):327-36. doi: 10.1016/j.pcd.2017.04.001 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Bovier PA, Sebo P, Abetel G, George F, Stalder H. Adherence to recommended standards of diabetes care by Swiss primary care physicians. Swiss Med Wkly 2007; 137(11-12):173-81. doi: 10.4414/smw.2007.11592 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Croteau K, Schofield G, McLean G. Physical activity advice in the primary care setting: results of a population study in New Zealand. Aust N Z J Public Health 2006; 30(3):262-7. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842x.2006.tb00868.x [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Daly B, Arroll B, Kenealy T, Sheridan N, Scragg R. Management of diabetes by primary health care nurses in Auckland, New Zealand. J Prim Health Care 2015; 7(1):42-9. [ Google Scholar]

- Davis-Ajami ML, Lu ZK, Wu J. Delivery of healthcare provider’s lifestyle advice and lifestyle behavioural change in adults who were overweight or obese in pre-diabetes management in the USA: NHANES (2013-2018). Fam Med Community Health 2021; 9(4):e001139. doi: 10.1136/fmch-2021-001139 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Desai MM, Rosenheck RA, Druss BG, Perlin JB. Receipt of nutrition and exercise counseling among medical outpatients with psychiatric and substance use disorders. J Gen Intern Med 2002; 17(7):556-60. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10660.x [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Eakin E, Brown W, Schofield G, Mummery K, Reeves M. General practitioner advice on physical activity--who gets it?. Am J Health Promot 2007; 21(4):225-8. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-21.4.225 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Egede LE, Zheng D. Modifiable cardiovascular risk factors in adults with diabetes: prevalence and missed opportunities for physician counseling. Arch Intern Med 2002; 162(4):427-33. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.4.427 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Eldemire-Shearer D, Holder-Nevins D, Morris C, James K. Prevention for better health among older persons: are primary healthcare clinics in Jamaica meeting the challenge?. West Indian Med J 2009; 58(4):319-25. [ Google Scholar]

- Foss FA, Dickinson E, Hills M, Thomson A, Wilson V, Ebrahim S. Missed opportunities for the prevention of cardiovascular disease among British hypertensives in primary care. Br J Gen Pract 1996; 46(411):571-5. [ Google Scholar]

- Geerling R, Browne JL, Holmes-Truscott E, Furler J, Speight J, Mosely K. Positive reinforcement by general practitioners is associated with greater physical activity in adults with type 2 diabetes. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care 2019; 7(1):e000701. doi: 10.1136/bmjdrc-2019-000701 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Hinrichs T, Moschny A, Klaassen-Mielke R, Trampisch U, Thiem U, Platen P. General practitioner advice on physical activity: analyses in a cohort of older primary health care patients (getABI). BMC Fam Pract 2011; 12:26. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-12-26 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Hu R, Hui SS, Lee EK, Stoutenberg M, Wong SY, Yang YJ. Provision of physical activity advice for patients with chronic diseases in Shenzhen, China. BMC Public Health 2021; 21(1):2143. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-12185-7 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Johansson K, Bendtsen P, Akerlind I. Advice to patients in Swedish primary care regarding alcohol and other lifestyle habits: how patients report the actions of GPs in relation to their own expectations and satisfaction with the consultation. Eur J Public Health 2005; 15(6):615-20. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cki046 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Juré J, Vuylsteke ME. Management of chronic venous disease in general practice: a cross-sectional study of first line care in Belgium. Int Angiol 2022; 41(3):232-9. doi: 10.23736/s0392-9590.22.04774-5 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Klumbiene J, Petkeviciene J, Vaisvalavicius V, Miseviciene I. Advising overweight persons about diet and physical activity in primary health care: Lithuanian health behaviour monitoring study. BMC Public Health 2006; 6:30. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-6-30 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Kriaucioniene V, Petkeviciene J, Raskiliene A. Nutrition and physical activity counselling by general practitioners in Lithuania, 2000-2014. BMC Fam Pract 2019; 20(1):125. doi: 10.1186/s12875-019-1022-8 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Lau JS, Adams SH, Irwin CE Jr, Ozer EM. Receipt of preventive health services in young adults. J Adolesc Health 2013; 52(1):42-9. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.04.017 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Gómez D, León-Muñoz LM, Guallar-Castillón P, López-García E, Aguilera MT, Banegas JR. Reach and equity of primary care-based counseling to promote walking among the adult population of Spain. J Sci Med Sport 2013; 16(6):532-8. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2013.01.006 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Nguyen HT, Markides KS, Winkleby MA. Physician advice on exercise and diet in a U.S. sample of obese Mexican-American adults. Am J Health Promot 2011; 25(6):402-9. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.090918-QUAN-305 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Robertson R, Jepson R, Shepherd A, McInnes R. Recommendations by Queensland GPs to be more physically active: which patients were recommended which activities and what action they took. Aust N Z J Public Health 2011; 35(6):537-42. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-6405.2011.00779.x [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Dos Santos LP, da Silva AT, Rech CR, Fermino RC. Physical activity counseling among adults in primary health care centers in Brazil. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021; 18(10):5079. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18105079 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Short CE, Hayman M, Rebar AL, Gunn KM, De Cocker K, Duncan MJ. Physical activity recommendations from general practitioners in Australia. Results from a national survey. Aust N Z J Public Health 2016; 40(1):83-90. doi: 10.1111/1753-6405.12455 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Shuval K, DiPietro L, Skinner CS, Barlow CE, Morrow J, Goldsteen R. ‘Sedentary behaviour counselling’: the next step in lifestyle counselling in primary care; pilot findings from the Rapid Assessment Disuse Index (RADI) study. Br J Sports Med 2014; 48(19):1451-5. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2012-091357 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Silagy C, Muir J, Coulter A, Thorogood M, Yudkin P, Roe L. Lifestyle advice in general practice: rates recalled by patients. BMJ 1992; 305(6858):871-4. doi: 10.1136/bmj.305.6858.871 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Sinclair J, Lawson B, Burge F. Which patients receive advice on diet and exercise? Do certain characteristics affect whether they receive such advice?. Can Fam Physician 2008; 54(3):404-12. [ Google Scholar]

- Smith BJ, Owen AJ, Liew D, Kelly DJ, Reid CM. Prescription of physical activity in the management of high blood pressure in Australian general practices. J Hum Hypertens 2019; 33(1):50-6. doi: 10.1038/s41371-018-0098-2 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- de Souza AL, Dos Santos LP, Rech CR, Rodriguez-Añez CR, Alberico C, Borges LJ. Barriers to physical activity among adults in primary healthcare units in the National Health System: a cross-sectional study in Brazil. Sao Paulo Med J 2022; 140(5):658-67. doi: 10.1590/1516-3180.2021.0757.r1.20122021 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Tiffe T, Morbach C, Malsch C, Gelbrich G, Wahl V, Wagner M. Physicians’ lifestyle advice on primary and secondary cardiovascular disease prevention in Germany: A comparison between the STAAB cohort study and the German subset of EUROASPIRE IV. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2021; 28(11):1175-83. doi: 10.1177/2047487319838218 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Wee CC, McCarthy EP, Davis RB, Phillips RS. Physician counseling about exercise. JAMA 1999; 282(16):1583-8. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.16.1583 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Znyk M, Zajdel R, Kaleta D. Consulting obese and overweight patients for nutrition and physical activity in primary healthcare in Poland. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022; 19(13):7694. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19137694 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Zwald ML, Kit BK, Fakhouri THI, Hughes JP, Akinbami LJ. Prevalence and correlates of receiving medical advice to increase physical activity in U.S. adults: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2013-2016. Am J Prev Med 2019; 56(6):834-43. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2019.01.003 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Countries. Available from: https://www.who.int/countries. Accessed April 11, 2023.

- Rivas-Ruiz F, Pérez-Vicente S, González-Ramírez AR. Bias in clinical epidemiological study designs. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr) 2013; 41(1):54-9. doi: 10.1016/j.aller.2012.04.005 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Hall LH, Thorneloe R, Rodriguez-Lopez R, Grice A, Thorat MA, Bradbury K. Delivering brief physical activity interventions in primary care: a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract 2022; 72(716):e209-e16. doi: 10.3399/bjgp.2021.0312 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Guthold R, Stevens GA, Riley LM, Bull FC. Worldwide trends in insufficient physical activity from 2001 to 2016: a pooled analysis of 358 population-based surveys with 1·9 million participants. Lancet Glob Health 2018; 6(10):e1077-e86. doi: 10.1016/s2214-109x(18)30357-7 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Mielke GI, da Silva ICM, Kolbe-Alexander TL, Brown WJ. Shifting the physical inactivity curve worldwide by closing the gender gap. Sports Med 2018; 48(2):481-9. doi: 10.1007/s40279-017-0754-7 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Global Status Report on Physical Activity 2022. Geneva: WHO; 2022.

- Lee IM, Shiroma EJ, Lobelo F, Puska P, Blair SN, Katzmarzyk PT. Effect of physical inactivity on major non-communicable diseases worldwide: an analysis of burden of disease and life expectancy. Lancet 2012; 380(9838):219-29. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(12)61031-9 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Rezende LFM, Garcia LMT, Mielke GI, Lee DH, Giovannucci E, Eluf-Neto J. Physical activity and preventable premature deaths from non-communicable diseases in Brazil. J Public Health (Oxf) 2019; 41(3):e253-e60. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdy183 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Warburton DE, Nicol CW, Bredin SS. Health benefits of physical activity: the evidence. CMAJ 2006; 174(6):801-9. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.051351 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Aittasalo M, Kukkonen-Harjula K, Toropainen E, Rinne M, Tokola K, Vasankari T. Developing physical activity counselling in primary care through participatory action approach. BMC Fam Pract 2016; 17(1):141. doi: 10.1186/s12875-016-0540-x [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Shuval K, Leonard T, Drope J, Katz DL, Patel AV, Maitin-Shepard M. Physical activity counseling in primary care: insights from public health and behavioral economics. CA Cancer J Clin 2017; 67(3):233-44. doi: 10.3322/caac.21394 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Verwey R, van der Weegen S, Spreeuwenberg M, Tange H, van der Weijden T, de Witte L. Upgrading physical activity counselling in primary care in the Netherlands. Health Promot Int 2016; 31(2):344-54. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dau107 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Wattanapisit A, Ng CJ, Angkurawaranon C, Wattanapisit S, Chaovalit S, Stoutenberg M. Summary and application of the WHO 2020 physical activity guidelines for patients with essential hypertension in primary care. Heliyon 2022; 8(10):e11259. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e11259 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Wattanapisit A, Poomiphak Na Nongkhai M, Hemarachatanon P, Huntula S, Amornsriwatanakul A, Paratthakonkun C. What elements of sport and exercise science should primary care physicians learn? an interdisciplinary discussion. Front Med (Lausanne) 2021; 8:704403. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.704403 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Varela AR, Pratt M, Harris J, Lecy J, Salvo D, Brownson RC. Mapping the historical development of physical activity and health research: a structured literature review and citation network analysis. Prev Med 2018; 111:466-72. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.10.020 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Wattanapisit A, Kotepui M, Wattanapisit S, Crampton N. Bibliometric analysis of literature on physical activity and COVID-19. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022; 19(12):7116. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19127116 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]